Every day, as we reach for our smartphone, launch our favourite TV series or send a business email, we participate in the quiet miracle of modern technology. Beneath the shiny surface of apps and services lies an invisible foundation – open source software.

It is millions of lines of code, written, refined and shared with the world for free by a global community. This code is the bloodstream of the internet and the backbone of the AI revolution.

But this digital world, raised on the idea of freedom and collaboration, conceals a profound paradox. The global economy relies on an infrastructure created largely by volunteers, often balancing on the brink of professional burnout.

It is as if global trade routes were based on bridges built as a hobby after hours. How long can such a structure last? Who actually pays for the code we all rely on?

The invisible foundation: our global dependence

Open source software is no longer an alternative. It has become the default building block of the digital world. Hard data paints a picture of almost total dependence. An analysis by Synopsys in 2024 showed that as much as 96% of the commercial code bases examined contained open source components.

What’s more, on average, 77% of all code in these applications came from open source. It’s no longer a question of using individual libraries – it’s about building entire systems on a foundation created by the community.

The scale of this dependency becomes even more striking when looking at the dynamics of consumption. In 2024, it was forecast that the total number of downloads of open source packages would reach the unimaginable figure of 6.6 trillion.

The npm (JavaScript) ecosystem alone was responsible for 4.5 trillion requests, recording 70% year-on-year growth, while the AI-powered Python ecosystem (PyPI) grew by 87% to reach 530 billion downloads.

The average commercial application today is a complex mosaic of an average of 526 different open source components. Each has its own life cycle, its own maintainers and its own potential problems.

Cracks in the foundation: zombie code and a wake-up call called Log4j

The ubiquity of open source is a double-edged sword. The same ease with which developers can incorporate off-the-shelf components into their projects leads to systemic neglect. The data is alarming: as many as 91% of the commercial code bases surveyed contain components that are ten or more versions out of date.

This problem leads to so-called ‘zombie code’ – components that have had no development activity for more than two years. This phenomenon affects almost half (49%) of the applications on the market.

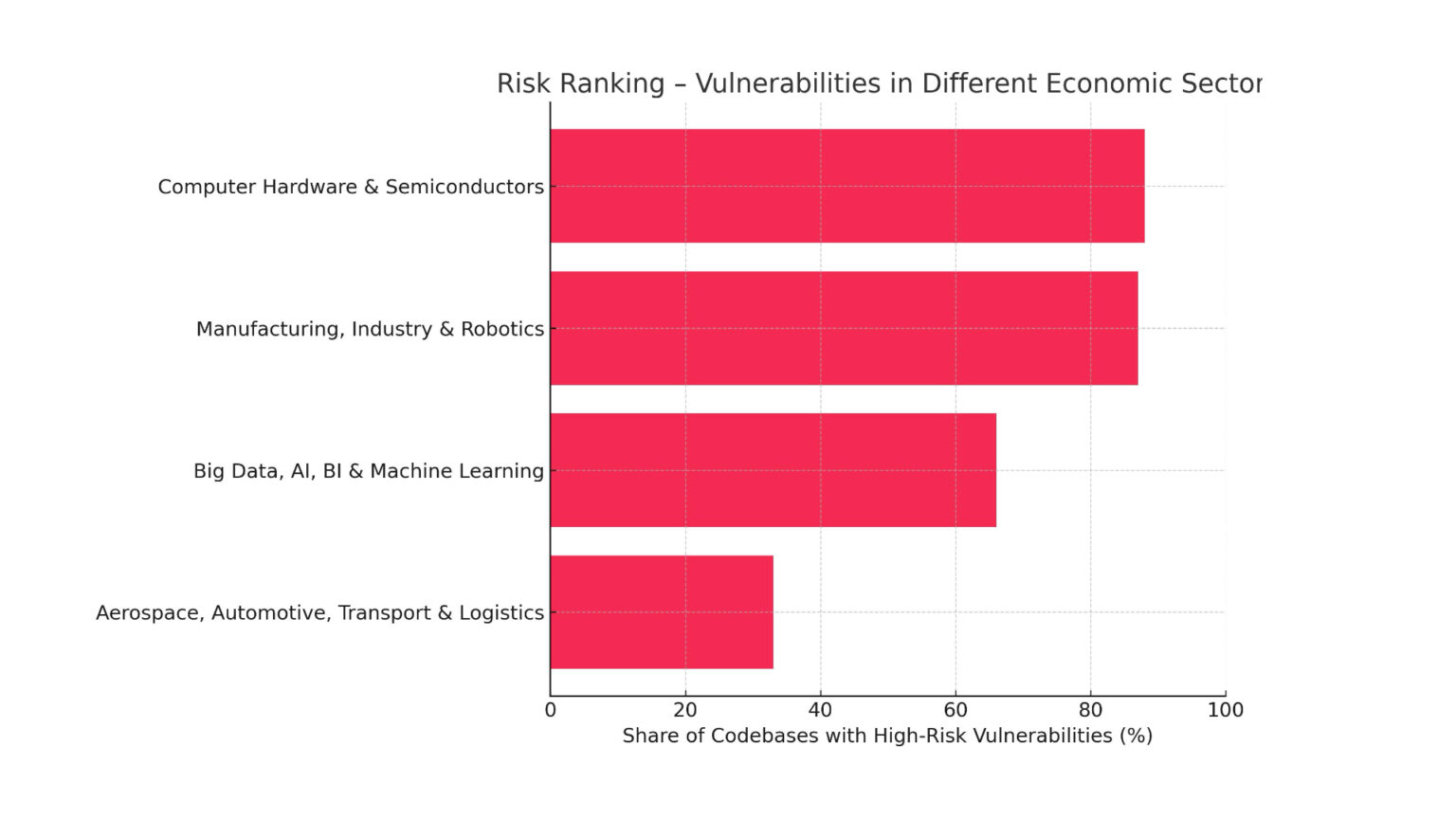

This means that companies are building their critical systems on abandoned projects, without active support and, most importantly, without security patches. The consequence is a ticking time bomb: in just one year, the percentage of code bases containing high-risk security vulnerabilities has increased from 48% to 74%.

Nothing illustrates this risk better than the December 2021 incident, when the world learned of the Log4j vulnerability. This small, free Java library for logging turned out to be embedded in millions of applications around the world.

The vulnerability, named Log4Shell, received a maximum criticality rating of 10/10. An attacker could take full control of a server by sending a simple string of characters. US CISA director Jen Easterly called it “one of the most serious vulnerabilities she has seen in her entire career”.

The Log4j incident became a global wake-up call, making companies brutally aware of how much their security depends on the work of anonymous volunteers.

Worse still, even three years after the discovery of Log4Shell, up to 13% of all Log4j library downloads are still vulnerable versions. This demonstrates the profound inertia of organisations that fail to update their dependencies even in the face of a well-known, critical threat.

The human cost of ‘free’ software: the burden of the custodian

There are people behind every line of code. A model that treats their work as a free resource generates a huge human cost. Salvatore Sanfilippo, the creator of the Redis database, described this phenomenon as the ‘flooding effect’.

Over time, the stream of emails, GitHub submissions and questions turns into a never-ending flood that leads to guilt over not being able to help everyone.

The scale of this pressure is illustrated by the example of Jeff Geerling, who looks after more than 200 projects. Each day he receives between 50 and 100 notifications, of which he is only able to deal with a fraction.

Nolan Lawson, another well-known maintainer, aptly put the emotional weight of this work. Notifications on GitHub are “a constant stream of negativity”. No one opens a notification to praise working code. People only post when something is wrong.

This chronic pressure leads to burnout, which, in the context of open source, has clearly defined causes: demanding users, low quality contributions, lack of time and, most acutely, lack of remuneration.

Knowing that work that consumes huge amounts of energy is the foundation for commercial products that make real profits for others is extremely demotivating. As one maintainer put it:

“My software is free, but my time and attention is not”. Caregiver burnout is not just a personal tragedy. It is a critical risk to the global infrastructure.

‘Zombie code’ is a direct, measurable symptom of this crisis at the human level.

The New Economy of Code: Towards a Sustainable Future

In the face of these risks, the open source ecosystem is slowly maturing, moving from a volunteer-based model to more sustainable forms of funding.

1. corporate patrons: strategy, not altruism

At the forefront of this transformation are the technology giants. Companies such as Google, Microsoft and Red Hat have been the biggest contributors to the open source world for years. Their motivations, however, are not altruistic – they are cold, strategic calculations.

Joint development of fundamental components (such as operating systems or containerisation) is simply more efficient. This allows them to compete at a higher level, in areas that directly differentiate their products.

By becoming involved in key projects, corporations can also influence their direction, ensuring alignment with their own strategy.

2 The power of institutions: the role of foundations

The second pillar is non-profit foundations such as the Linux Foundation and the Apache Software Foundation. They act as neutral trustees for the most important projects, ensuring their stability and independence from a single corporation.

They collect contributions from sponsors, creating a budget that allows them to fund key developers and safety audits.

3 The maker revolution: the GitHub Sponsors model

Alongside the big players, a new grassroots funding wave has been born. Platforms such as GitHub Sponsors allow direct, recurring contributions from users and companies, creating a revenue stream for maintainers.

The story of Caleb Porzio, creator of Livewire and AlpineJS tools, is a prime example of the potential of this model. Standing on the brink of burnout, he decided to try his hand at the GitHub Sponsors programme.

The real breakthrough came when he changed the paradigm: instead of asking for support, he decided to offer his sponsors additional, exclusive value. His secret turned out to be paid screencasts – a series of video tutorials.

He reserved access to the full library exclusively for backers on GitHub. The effect was spectacular. His annual revenue grew by $80,000 in 90 days and crossed the $1 million threshold in the following years.

This is a key lesson: a sustainable model does not have to be based on charity, but on building a viable business model around a free, open core.

From stowaway to stakeholder

‘Free’ software has never been free. Its price, hitherto hidden, has been paid with the time, energy and mental health of a global army of volunteers. The model in which we treated their work as an inexhaustible resource is coming to an end.

It is time for every participant in this ecosystem to undergo a transformation – from a passive ‘stowaway’ to an active stakeholder.

This requires specific actions. Developers need to practice ‘software hygiene’ – regularly updating dependencies and consciously managing technical debt.

Companies need to treat open source as a critical part of the supply chain, creating ‘software component inventories’ (SBOMs) and investing in business-critical projects. Investing in open source is not a cost, it is business continuity insurance.

We stand at the threshold of a new era for open source – an era of professionalisation and sustainability. A future where creators are fairly remunerated and the global digital infrastructure is secure is within our reach. Building it, however, requires a conscious effort from each of us.