For years, the Polish IT sector has been presented as the jewel in the crown of the national economy. It is an engine of innovation, a key exporter of services and a symbol of successful transformation. The data seem to confirm this optimistic picture: the industry accounts for a significant proportion of GDP and forecasts predict further dynamic growth in the value of the market.

However, beneath the shiny surface of success, a threatening wave is rising that is hitting the foundations of this ecosystem. Thousands of smaller companies and sole traders are facing unprecedented financial pressures and their debts are growing at an alarming rate, reaching hundreds of millions.

This raises a fundamental question that defines the current moment in the market: how is it possible that a sector that is a national champion simultaneously becomes a graveyard for small businesses? The answer to this paradox is complex and multidimensional.

We are witnessing the end of the post-pandemic ‘Eldorado’ era – a period in which almost every entity, regardless of scale and efficiency, could count on orders. Today we are entering a new, more brutal phase of market maturity, characterised by ruthless natural selection.

Landscape after the eldorado: Decline and debt

The picture of the Polish IT sector, painted by headlines and general economic indicators, often overlooks the murky reality faced by its most fragmented part.

Analysis of data from public registers and business information bureaus reveals a worrying trend of increasing financial pressures, leading to a wave of business closures, bankruptcies and exponentially increasing debt. This is hard evidence that the golden days are over for many players.

Although the overall number of active businesses in Poland remains high , data from the Central Register and Information on Economic Activity (CEIDG) show the other, less optimistic side of the coin.

In recent years, there has been a marked increase in the number of applications to close and suspend sole proprietorships . These figures are a wake-up call, indicating worsening conditions for the smallest entrepreneurs, who are the backbone of the IT sector.

In addition to de-registrations from CEIDG, which are often quiet disappearances from the market, the number of formal insolvency and restructuring proceedings visible in the National Court Register (KRS) is also increasing.

Figures from recent years show a steady increase in the number of companies forced to declare bankruptcy. Although these figures apply to the economy as a whole, the IT industry is over-represented in them. According to analyses, the technology sector ranks among the top in terms of the number of bankruptcies and restructurings in the country.

This is therefore not a picture of the apocalypse, but rather evidence of a painful market correction in which players with weaker business foundations are eliminated after a period of artificially driven demand.

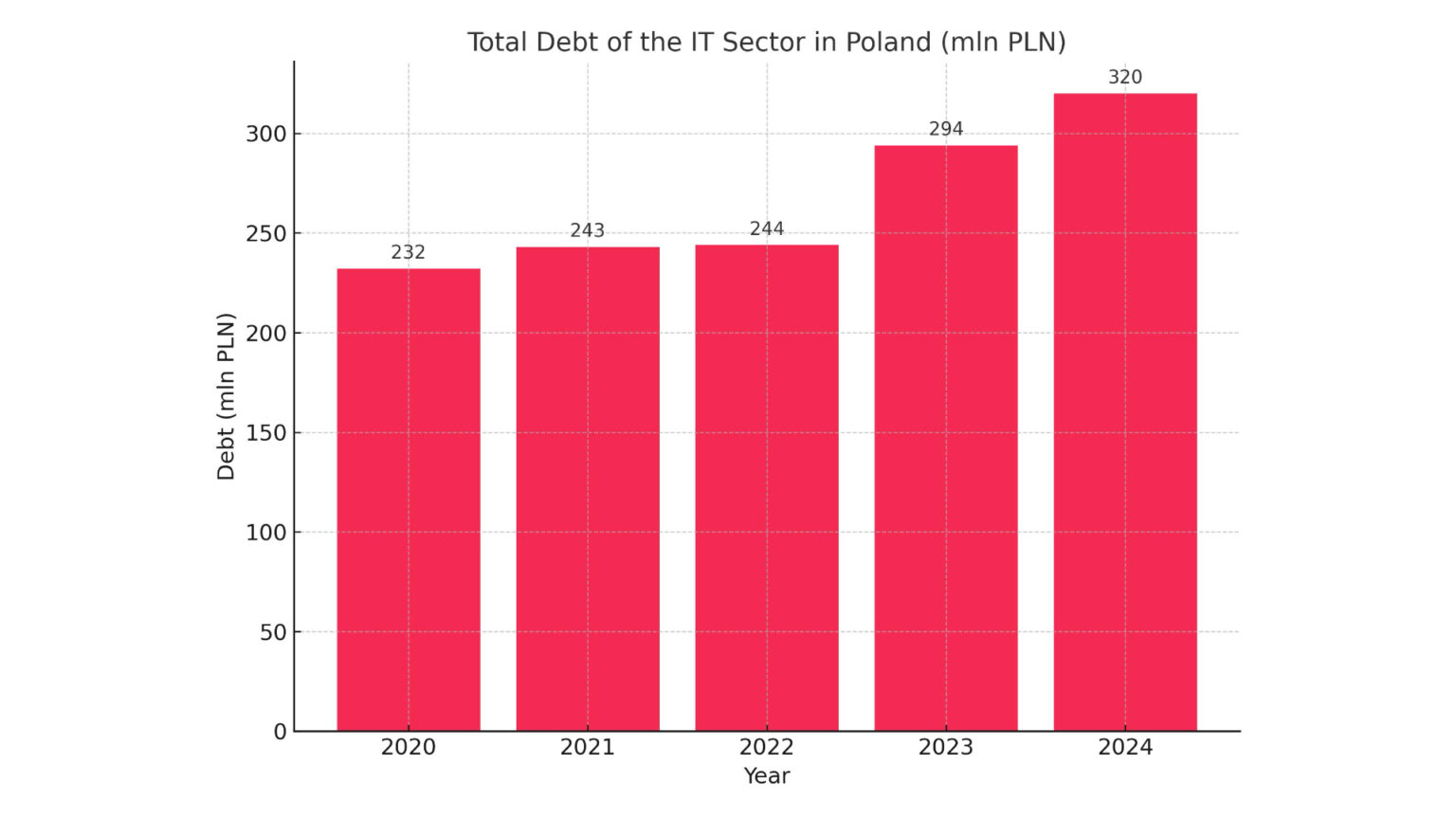

The most telling indicator of the crisis, however, is the explosion of debt in the industry. Data from the National Debt Register (KRD) is alarming. Over the past two years, the total debt of IT companies has increased significantly, reaching hundreds of millions of PLN . During this time, the number of indebted IT entities has also increased, as has the average debt per company.

Central to understanding the nature of this crisis is the breakdown of debt into legal forms of activity. This is where the extreme vulnerability of the smallest players becomes apparent. The data shows that sole traders account for a significant proportion of the industry’s total debt.

This disparity is indicative of the fragility of the self-employment business model, which becomes a financial trap during the downturn .

The problem is exacerbated by the domino effect caused by payment bottlenecks. The IT industry is not only a debtor, but also a significant creditor. IT companies are waiting to be repaid hundreds of millions of zlotys from their counterparties.

The main debtors in the IT sector are companies from the retail, construction and transport sectors. This mechanism creates a vicious circle: a large customer delays payment, which deprives a small software house of liquidity, which is consequently unable to settle its own obligations. Small companies, deprived of the financial cushion available to large integrators, become the first victims of this debt spiral .

Time of the giants: Consolidation and financial dominance

While thousands of small companies are struggling to survive, at the other end of the market a completely different spectacle is playing out. The biggest players – the mighty systems integrators and distributors – are not only not feeling the crisis, but are actually consolidating their dominance.

Their financial strength, strategic acquisitions and diversified portfolio allow them to prosper in conditions that are lethal for smaller players. This is the era of the giants, who are actively shaping the new, consolidated landscape of Polish IT.

The top of the Polish IT market is made up of a relatively small group of companies whose scale of operations puts them in a completely different category from the rest of the industry. We are talking about entities such as the Asseco Poland Group, the Comarch Group, distributors AB and ALSO, or integrators such as Integrated Solutions .

Their power is best seen in financial data. The revenues of Poland’s largest IT companies exceed the estimated value of the entire IT market in the country, which clearly shows that it is dominated by dozens of entities that control the lion’s share of it, creating a clear financial hierarchy.

A key element of the growth strategy of these giants is market consolidation through mergers and acquisitions (M&A). Analytical reports clearly indicate that the TMT sector (Technology, Media, Telecommunications) is the most active battleground on the Polish M&A market . P

ioner and model example of such a strategy is Asseco Poland. For years, the company has consistently built its power by acquiring key players in the market . These historic mergers allowed Asseco not only to leapfrog in scale, but also to diversify its competences and enter new market segments.

Recent events signal a new, more mature phase of consolidation. The acquisition of Comarch, Poland’s second software giant after Asseco, by a global private equity fund in partnership with the founder’s family, is a landmark deal.

This is no longer just consolidation within the Polish market. The entry of such a powerful financial player shows that the Polish IT sector has reached a maturity and attractiveness that attracts major international capital. This transaction heralds an acceleration of consolidation processes and even greater pressure on smaller, less efficient competitors.

In contrast to small companies balancing on the brink of liquidity, large integrators are strongholds of financial stability. An analysis of their financial statements shows not only resilience in the face of a downturn, but often also improved profitability.

The strength of these companies is also confirmed by investor confidence. The regular and generous dividends attest to their stable financial condition and the boards’ confidence in their positive future prospects.

The structural advantage of the giants is also due to their evolution. Through years of acquisitions and organic growth, these companies have evolved into diversified technology conglomerates . This diversification is a powerful protective shield.

A downturn in one area can easily be offset by stable, recurring contract revenues in another sector. This kind of resilience to business cycles can almost never be achieved by a small, specialised company.

Anatomy of survival: Why do the small fail and the big grow?

The observed phenomena – the wave of bankruptcies of small companies and the simultaneous growth in the power of integrators – are not a coincidence. They are the logical consequence of fundamental economic forces that operate with redoubled force in times of market correction.

For smaller players, the current market environment has become a battleground for survival. The post-pandemic boom period is over and the market has returned to more sustainable levels of demand.

As a result, more players are competing for fewer orders, which inevitably leads to a tougher price battle . At the same time, small companies are particularly sensitive to rising operating costs.

The salary pressures that dominated the market in previous years have left a lasting mark in the form of high financial expectations of professionals . Small software houses are finding it difficult to compete for talent with the giants.

Moreover, the structural weakness of small businesses lies in their lack of capital reserves. Dependence on a few key customers and vulnerability to payment bottlenecks mean that even a slight delay in paying an invoice can shake liquidity.

Finally, the most lucrative and stable revenue streams – multi-year, multi-million dollar contracts from the public sector and large corporations – remain out of their reach due to formal and capital barriers.

At the same time, the big players use the same market conditions to their advantage. Their fundamental advantage is economies of scale. A large integrator, buying hundreds of software licences or servers, obtains much better pricing terms from manufacturers.

A diversified portfolio of services and customers acts like an insurance policy, balancing risk . Stable financial performance opens up access to low-cost financing for giants, enabling not only investment in growth but also strategic acquisitions of weakened competitors.

At the same time, they are able to attract and retain the best professionals, which further strengthens their competitive advantage.

As a result of these processes, we are witnessing a profound transformation of the market. It is no longer a unified ecosystem, but rather two parallel worlds. The first is the integrator market, characterised by large-scale projects and M&A strategies.

The second is a fragmented and highly competitive niche market, with thousands of small companies and freelancers competing for smaller assignments. This is not an industry-wide crisis, but a painful but classic stage of economic maturity.

Consequences and prospects: What does the future hold for Polish IT?

The processes of polarisation and consolidation we are currently witnessing are not just a temporary anomaly. They are fundamental forces that are reshaping the entire Polish IT ecosystem, with long-term consequences.

The balance of power is shifting in the labour market. In an environment where cost-cutting dominates, companies have less incentive to invest in training entry-level employees, creating a barrier to entry for juniors.

Although IT salaries are still at a high level, their explosive growth has slowed down and employers are becoming more demanding. The real value and highest salaries are now offered by the highly specialised fields in which the major players are investing heavily: artificial intelligence, cyber security, data analytics and cloud computing.

The impact of increasing market concentration on innovation is ambiguous. On the one hand, large corporations have resources for research and development, which can accelerate the commercialisation of innovations.

On the other hand, the history of technology teaches that revolutionary ideas are often born in small, agile start-ups. Excessive market concentration threatens the emergence of oligopolies that can impede progress . The challenge for Poland will be to maintain a balance between these two forces.

In the new polarised reality, survival and growth strategies must be redefined. For small companies, hyper-specialisation in a narrow market niche is becoming the only viable growth path. For large integrators, the main challenge will be to maintain the capacity for innovation and agility.

Looking to the future, the Polish IT market is not shrinking, but evolving into a more mature sector that is integrated into the global economy. The future will be determined by megatrends such as artificial intelligence, ubiquitous digitisation and the growing importance of cyber security.

Success will depend not so much on swimming with the tide of overall growth, but on precise strategic positioning and operational excellence.

The analysis of market trends reveals the Polish IT sector at a moment of transformational change. The apparent paradox of simultaneous waves of bankruptcies and the growing dominance of giants turns out to be two sides of the same coin: a painful but inevitable process of market maturation. The golden era of the popandemic boom is irrevocably gone, giving way to a more challenging reality.

For thousands of small companies, this means a struggle for survival. At the same time, the largest integrators are taking advantage of these conditions to strengthen their position by actively accelerating market consolidation through strategic mergers and acquisitions .

As a consequence, the Polish IT sector is evolving into a more structured industry integrated with global capital. This transformation, although painful for many, may in the long term lead to a stronger and more internationally competitive sector.

However, it will be dominated by a few powerful players, with space left for highly specialised, agile niche companies.

Survival and success in this new reality will require all market players to redefine their existing strategies and adapt to the ruthless laws of a mature economy.