In the common perception of executives, artificial intelligence appears as an ethereal, almost metaphysical entity. We see it through the prism of algorithmic elegance and the infinite scalability of the cloud, forgetting that every query sent to a language model initiates a cascade of events in the most material world possible. The latest market data forces us to brutally revise this digital idealism. For it turns out that the biggest brake on the modern economy is not a shortage of creative programmers, but hard infrastructure constraints: a lack of copper, a shortage of power in transmission networks and, most acutely, a dramatic shortage of manpower in professions that have so far rarely been on the agenda of technology company board meetings.

The scale of this challenge is illustrated by the dynamics of energy forecasts. When, in just seven months, BloombergNEF analysts revise projected energy demand for data centres upwards by more than a third, it becomes clear that strategic planning in the IT sector has entered a terrain of high uncertainty. The projected 106 gigawatts of power consumption in the US infrastructure alone by 2035 is not just an engineering challenge, it heralds a new era in which computing power will become a scarce good, rationed by the physical capacity of transformers and the availability of technical staff.

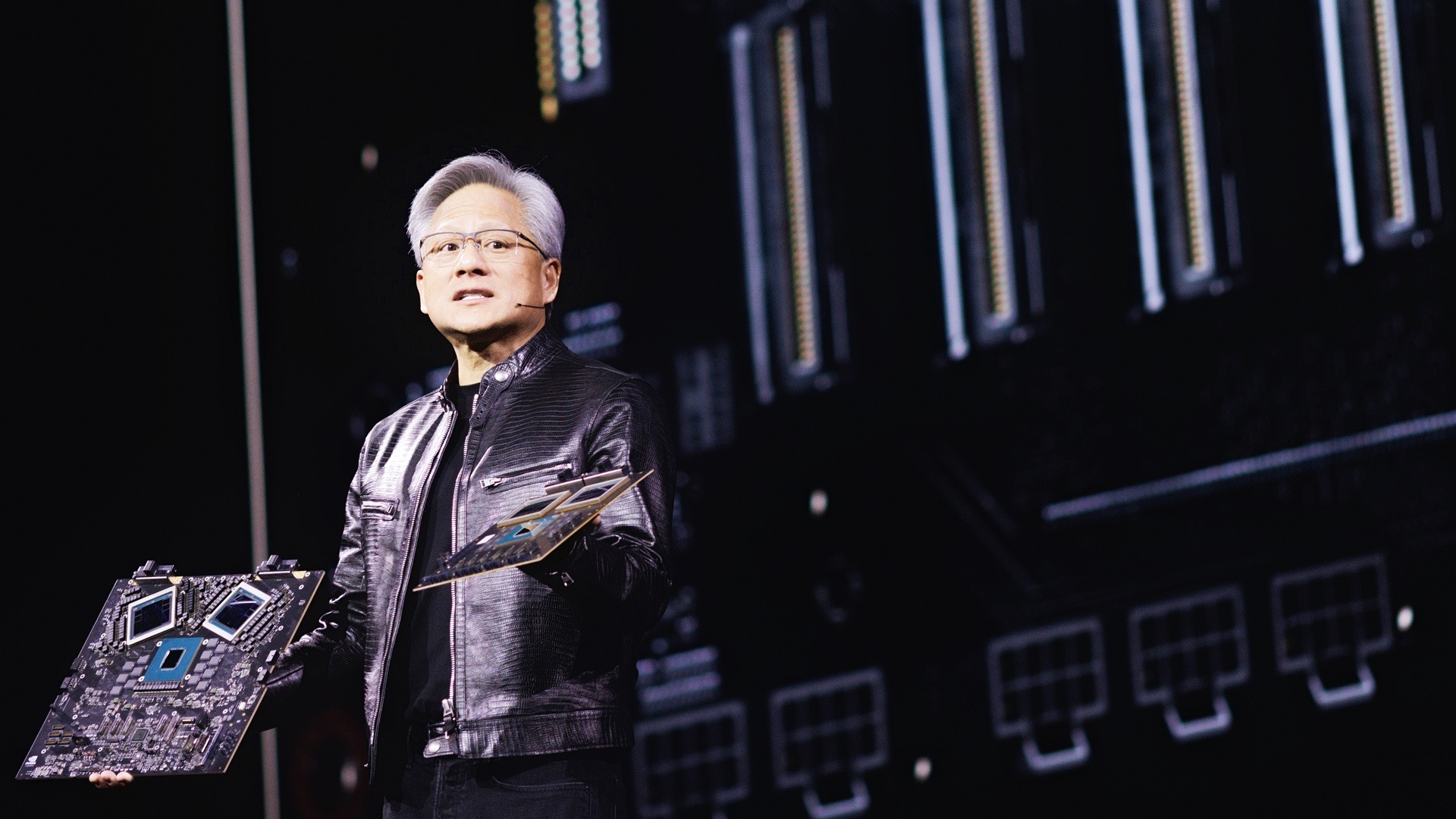

We are entering a period where the ‘fluidity’ of digital innovation is colliding with the ‘stickiness’ of real-world investment processes. Although the construction of AI data centres is progressing at an unprecedented pace, developers are encountering a glass ceiling that cannot be broken through with code optimisation. This problem is analysed by IEEE Spectrum, among others, pointing to a dangerous skills gap. While the labour market has been saturated with abstraction-layer specialists for years, the real technology base – server rooms, cooling systems and high-voltage networks – has begun to suffer from a chronic shortage of qualified structural, mechanical and electrical engineers.

This paradigm shift is redefining the concept of ‘IT talent’. The traditional battle for developers is giving way to a much tougher battle for multi-tasking infrastructure operators. Data from the AFCOM report suggests that, for more than half of data centre managers, it is operations staff and physical security specialists who are the bottleneck to growth today. We need experts who can manage critical high-density liquid cooling systems with the same agility as their software colleagues manage databases. Unfortunately, the need for these competencies is growing at a time when the global electricity grid is undergoing its most serious upgrade in decades, leaving the AI sector to compete with the renewable energy and industrial construction industries for the same engineers.

In response to these deficits, technology hegemons such as Microsoft, Google and Amazon are beginning to take on roles traditionally assigned to state education systems. The creation of their own academies and partnership programmes with technical schools is not a sign of philanthropy, but a pragmatic attempt to secure the competence supply chain. There is a lesson here for medium-sized market players about the need for a deep review of business resilience strategies. The success of AI deployment will increasingly depend on the ability to secure the physical resources and technical competencies that guarantee the continuity of systems in a world with rising energy and water costs.

Ultimately, the issue of sustainability ceases to be the domain of PR departments and becomes the foundation of risk analysis. The increasing consumption of water to cool servers and the drastic differences in the carbon footprint of different geographical regions make the choice of infrastructure partner an ethical and financial decision. A lack of awareness regarding where the energy powering our AI models is coming from and who is looking after their physical performance can become a costly oversight. The future of business belongs to those leaders who can look beyond the monitor screen and see that their digital ambitions are inextricably intertwined with the fate of the engineer working on high-voltage systems.

For years, we have lived in a paradigm where software has ‘eaten the world’, suggesting that hardware is merely a cheap and replaceable base. The AI revolution is reversing this vector. Today, it is the availability of physical infrastructure that dictates the pace of digital innovation. For business leaders, this means going back to the roots of operational planning: securing scarce resources, investing in people with specific physical skills and taking responsibility for the entire technology lifecycle – from water intake in cold storage to the energy mix of the local grid. It is a lesson in humility towards the physical world that will ultimately determine who emerges victorious from the race for supremacy in the age of algorithms.