The artificial intelligence revolution, long heralded in boardrooms and research labs, is finally starting to take shape in the European business landscape.

The data shows an unprecedented acceleration that suggests that companies on the Old Continent are opening up to new technologies en masse. However, beneath the surface of these impressive figures lies a much more complex and nuanced picture.

The key question is whether we are witnessing a deep, transformational wave that will lift the entire economy, or rather a concentrated wave that bypasses most businesses

The latest Eurostat figures provide the starting point for this analysis. In 2024, 13.5% of businesses in the European Union (with 10 or more employees) will be using artificial intelligence technology.

At first glance, this figure may seem modest, but its true significance is revealed when compared to the previous year. In 2023, the rate was only 8.0%.

This represents an increase of 5.5 percentage points in just twelve months – a dynamic that has almost doubled the overall level of AI adoption across the Union. Such a sharp jump signals that barriers to entry are falling and companies are seeing increasingly tangible benefits from implementing intelligent systems.

However, before declaring AI a universal triumph, it is important to look at the other side of the coin. A rate of 13.5% also means that the overwhelming majority, more than 86% of European companies, are still not using AI in their operations.

This shows how far we are from widespread implementation. Moreover, this growth needs to be put in a global context, where Europe is often seen as lagging behind the US and China in terms of both investment and scale of AI deployments.

This perspective adds urgency to understanding the nature of the current spurt. There is a real risk that Europe, by focusing on regulation, may miss out on the ‘historic wave of wealth creation’ driven by the rapid and widespread deployment of AI in other parts of the world.

So what is driving this sudden increase? Analysis of the data suggests that this is no coincidence. The surge in adoption between 2023 and 2024 correlates perfectly with the explosion in popularity of generative artificial intelligence, epitomised by ChatGPT, which was released to the general public in late 2022.

Further data shows that language processing technologies such as text mining and natural language generation have seen the greatest growth. This leads to the conclusion that the current wave of adoption is largely driven by more readily available, often off-the-shelf language applications, rather than the sudden widespread deployment of complex, deeply integrated machine learning systems.

This is where the ‘hype’ around generative AI is transforming into the first real business applications, lowering the threshold of entry for many companies that previously saw AI as too complex and expensive a technology.

Europe’s AI map: a continent full of contrasts

A geographical analysis of artificial intelligence deployments in the European Union reveals a picture of a deeply divided continent. Instead of a united front of technological progress, we see clear clusters of leaders, a group of marauders, and key economies that position themselves in the middle.

This map of contrasts is key to understanding where AI is already a business reality and where it remains only an aspiration.

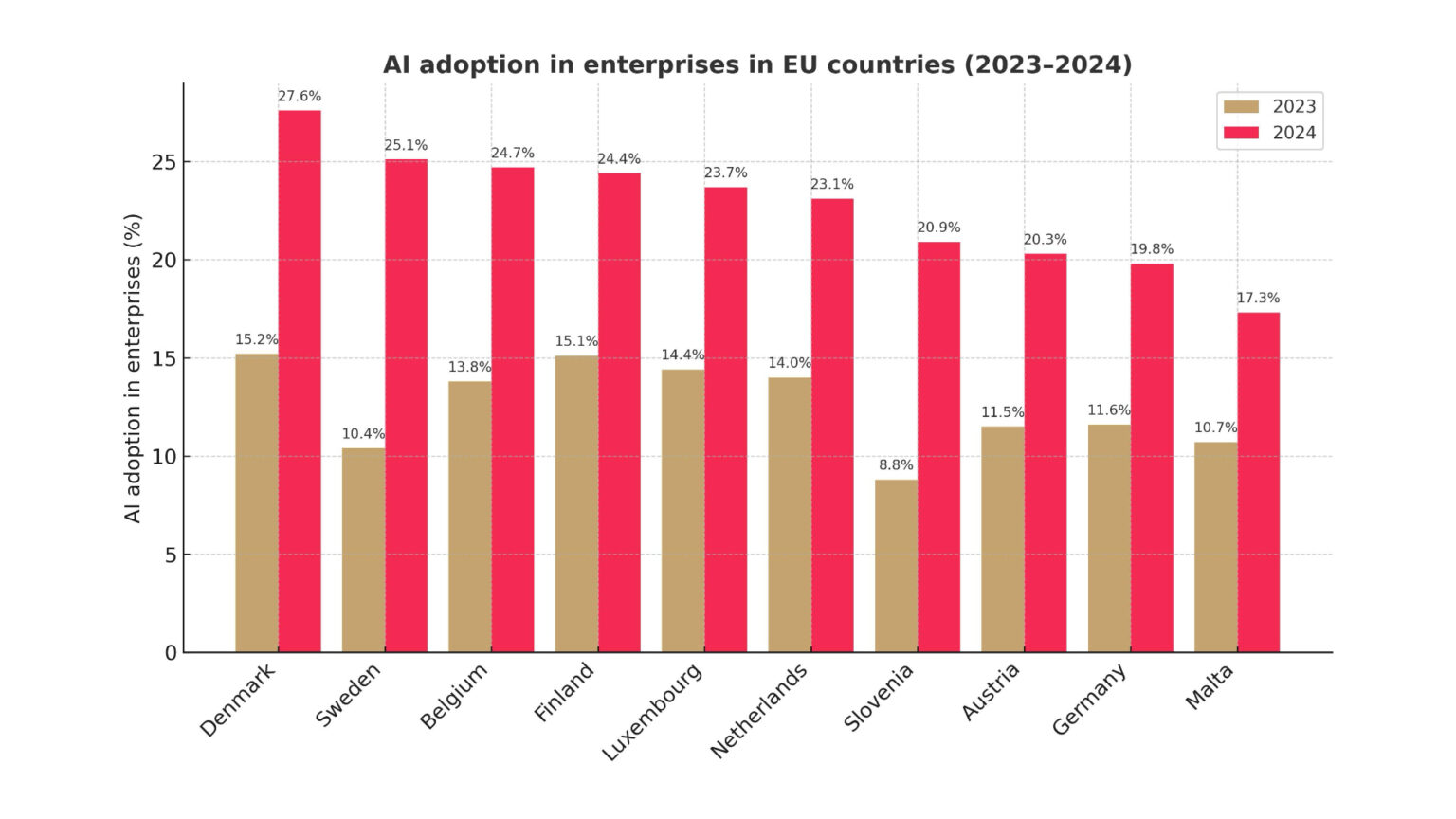

At the head of the peloton is a clear bloc of Nordic and Benelux countries, which are setting the pace for the rest of the continent. Denmark is the undisputed leader in the EU, with an AI adoption rate of 27.6%.

This is closely followed by Sweden (25.1%) and Belgium (24.7%). Finland (24.4%) and Luxembourg (23.7%) are also in this top group. It is noteworthy that the rates in these countries are more than double the EU average, demonstrating their digital sophistication and maturity.

At the other extreme are the countries of Eastern and Southern Europe, where AI adoption is progressing much more slowly. Romania closes the rate with the lowest rate in the entire Union, at just 3.1 per cent.

The situation is not much better in Poland (5.9%) and Bulgaria (6.5%), which also lag significantly behind the average. This gap between leaders and laggards is not static – it is widening. Growth dynamics show that the leaders are accelerating even further. Sweden recorded the highest annual growth (+14.7 p.p.), closely followed by Denmark (+12.4 p.p.) and Belgium (+10.9 p.p.). At the same time, countries such as Portugal (+0.8 p.p.) and Romania (+1.6 p.p.) are growing at a much slower pace, making the gap to the top ever wider.

Europe’s largest economies present a more mixed picture. Germany, with a score of 19.8%, ranks well above the EU average. The case of France is surprising.

Despite being a European leader in the development of advanced AI models (with 3 influential models coming from France in 2024), the adoption rate of AI in companies there is one of the lower ones, at just 9.9%. Spain also scores a modest 11.3%.

The case of France sheds light on a key paradox: the discrepancy between innovation potential and market implementation. Having strong R&D centres and the capacity to create advanced technologies does not automatically translate into widespread business adoption.

The low adoption rate in France suggests barriers to the internal market. These could be regulatory obstacles, a risk-averse business culture, or a gap in the skills needed to implement, rather than just create, AI.

This shows that a thriving innovation ecosystem, consisting of startups and research labs, does not guarantee that the wider business ecosystem, especially small and medium-sized enterprises, will integrate these innovations.

The path from the laboratory to the production floor is clearly narrowed in this case. There is an important lesson for policymakers: supporting research and development is not enough; a parallel strategy is needed to stimulate demand and facilitate market deployment.

The great divide: why are large companies overtaking SMEs?

One of the most striking findings from the data is the huge gap in AI adoption between large corporations and the small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) sector.

This divergence is so significant that it threatens to create a bipolar economy in Europe, with technological leaders pulling away from the rest of the peloton, exacerbating inequalities in productivity and competitiveness.

The figures speak for themselves. As many as 41.2% of large companies (with 250 or more employees) are actively using AI technology. This rate drops sharply to 20.9 per cent for medium-sized companies and reaches just 11.2 per cent in small companies (with 10 to 49 employees).

What’s more, the rate of growth in large companies is also higher – their share of AI adoption has increased by more than 10 percentage points over the past year, further widening the existing gap.

Eurostat points to three fundamental reasons for this disparity: implementation complexity, economies of scale (larger companies benefit more from automation and optimisation) and cost (large organisations have significantly more capital to invest in new technologies).

These factors are reinforced by a strategic approach. Companies with a clearly defined and visible AI strategy are twice as likely to achieve AI-driven revenue growth – and the ability to do such strategic planning is much more common in large corporations.

However, this disparity is not purely financial. Large companies have a key strategic advantage: the vast resources of their own data and the ability to attract rare and expensive AI talent.

This creates a self-perpetuating cycle, a kind of ‘moat’ separating them from smaller competitors. More data allows them to train better, more effective AI models. These, in turn, generate further data and revenue, allowing the best specialists to be hired.

Small and medium-sized companies are often outside this virtuous cycle. AI systems, especially those based on machine learning, require huge data sets to operate effectively. Large companies naturally generate and control much more data than SMEs.

At the same time, a major barrier to adoption is the lack of skills and expertise. The best AI professionals are a limited and expensive resource. Large, recognisable brands with adequate budgets and ambitious projects easily attract this talent, while SMEs find it difficult to compete for them.

As a result, the AI adoption gap among SMEs is not just a temporary lag, but a structural barrier, rooted in the fundamental requirements of AI technologies (data and talent). Without targeted policy interventions, such as data-sharing initiatives or training programmes for SMEs, this gap is likely to widen, leading to significant productivity gaps across the European economy.

Sector spotlight: where AI is already an everyday business reality

Having identified geographical and organisational leaders, the analysis moves to the sectoral level, answering the question: in which industries has AI taken deepest root? The data clearly shows that the AI revolution, at least for the time being, is a phenomenon heavily concentrated in the digital and knowledge-based sectors.

For many traditional industries, artificial intelligence is still a distant future.

The undisputed leader is the information and communication (ICT) sector, where as many as 48.7 per cent of companies are actively using AI technologies. This is almost four times the EU average and shows that AI is becoming a business standard in this industry. In second place, at a significant loss, is the professional, scientific and technical activities sector, with a still impressive adoption rate of 30.5%.

Outside these two leaders, there is a sharp decline. All other sectors of the economy have AI adoption rates below 16%. Traditional industries such as construction show minimal interest, with implementations at just 6.1%.

This polarisation is directly related to the nature of the industries themselves. The ICT and professional services sectors are inherently data-rich and digitally mature. Applications of AI for data analytics, process automation or content generation are obvious and relatively easy to implement in them.

The AI adoption map coincides almost perfectly with the digital maturity map. Sectors that have already undergone significant digital transformation provide fertile ground on which AI is now taking root.

From this, it follows that for traditional industries such as construction or manufacturing, the main challenge may not be AI technology itself, but the more fundamental lack of digitalisation and data infrastructure.

Effective AI implementation requires a robust data infrastructure, data management skills and digitised business processes. Traditional sectors often lag behind in these basic digital capabilities.

Therefore, decision-makers and companies in these industries cannot simply ‘implement AI’. They must first address the foundations of digitalisation. The challenge of AI adoption is in many cases symptomatic of a deeper digital maturity gap. Trying to impose AI solutions on companies that do not have a basic data infrastructure is a recipe for failure.

Beyond the trendy buzzwords: what AI technologies are European companies actually using?

This section separates the marketing hype from the business reality, looking at which specific AI tools are being deployed in European companies. It turns out that the current boom is overwhelmingly driven by language technologies, reflecting a fundamental shift in the market and the powerful impact of generative artificial intelligence.

In 2024, the most used AI technology in the EU is text mining, or written language analysis, used by 6.9% of all companies. This is closely followed by natural language generation (NLG), used by 5.4% of companies, and speech recognition (4.8%).

This is a significant change from 2023, when workflow automation was the most popular technology (3%) and NLG was used by only 2.1% of companies. In one year, the use of text mining and NLG has more than doubled, which is direct evidence of the impact of the AI generative revolution.

What are companies using these tools for? The main business purpose of AI implementations is marketing and sales (34.1% of companies using AI), followed by the organisation of administrative and management processes (27.5%).

These applications are ideally suited to the capabilities of language models, which excel at creating marketing content, communicating with customers (chatbots) and summarising information.

In contrast, more complex applications, such as machine learning for data analytics, are used by a smaller percentage of companies overall, although it is the second most popular technology among large enterprises.

The dominance of technologies such as text mining and NLG suggests that much of the current wave of adoption represents ‘shallow integration’. These are often standalone tools or APIs incorporated into existing processes – for example, the use of generative AI for marketing text writing.

This is quite different from ‘deep integration’, which would involve re-engineering a key production process based on a predictive machine learning model. The dominant technologies are language-based and often available as off-the-shelf software.

The main application areas are support functions such as marketing and administration, rather than key operations in most industries. Deep integration, such as the use of machine learning in manufacturing processes, requires significant data engineering, custom modelling and process redesign, which is much more complex and costly.

This is borne out by the Accenture report, which shows that in Europe, only 8% of large-scale investments in AI to transform business operations have been implemented at scale, with many companies stuck in the ‘pilot phase’. The conclusion is clear: increasing the adoption rate to 13.5% is real, but it is heavily skewed towards easier-to-implement, shallowly integrated tools. This is a key distinction between hype and reality. While many companies are using AI today, far fewer are fundamentally transformed by it.

Anatomy of a leader: an in-depth analysis of Denmark’s AI strategy

To understand what drives success in AI adoption, it is worth taking a closer look at the undisputed leader of the European Union – Denmark. The Danish case study shows that the top ranking is not a coincidence, but the result of a proactive, coherent and well-funded national strategy.

This case study can serve as a model for other countries seeking to accelerate their digital transformation.

The result speaks for itself: with a 27.6% adoption rate of AI in companies, Denmark is far ahead of the rest of the EU. Behind this success is the national ‘AI Strategy’, launched in 2019 and strengthened in 2023.

It is not just a policy document, but a concrete action plan, backed by dedicated funding of €200 million for research and development.

Denmark’s strategy is based on several key pillars, which together form a coherent innovation-friendly ecosystem:

- Ethical and human-centred foundation: from the outset, the Danish strategy emphasises the creation of a common ethical framework for AI. It focuses on trust, citizen self-determination and respect for human dignity. This approach builds both social and business trust, reducing one of the key barriers to adoption.

- Targeting key sectors: rather than dispersing efforts, the strategy identifies priority areas where AI can make the most difference: healthcare, energy, agriculture and transport. This allows for the concentration of resources and the creation of specialised solutions.

- Support for business, especially SMEs: The strategy includes specific initiatives to support companies. Examples are the Danish Growth Fund investment fund, aimed at companies basing their business model on AI, and the ‘Sprint:Digital’ programme, which helps SMEs with digital transformation.

- Public sector leadership: One of the main goals is for the public sector to use AI to offer ‘world-class services’. This creates internal demand for innovation, promotes best practice and demonstrates the benefits of the technology.

- Emphasis on collaboration: The Danish strategy promotes the creation of a collaborative ecosystem, especially with dynamic startups. A similar approach can be seen in another leader, Belgium, where up to 90 per cent of companies see collaboration with startups as crucial to the development of AI.

Denmark’s success suggests that a proactive, investment-driven national strategy, focused on building a supportive ecosystem, is more effective in driving adoption than a pan-European approach that often puts regulation first.

While the EU AI Act aims to create a single, trusted market, its complexity can generate uncertainty in the short term and slow down adoption. The Danish model focuses on building capacity and trust from the ground up.

Denmark has a clear, well-funded and holistic AI strategy ahead of the full implementation of EU legislation. At the same time, some sources point to legal uncertainty and over-regulation as potential barriers to adoption in the wider European context.

Leadership in AI adoption is therefore no accident. It is the result of a conscious, well-implemented national industrial policy. The Danish case proves that the government can actively shape the market and create an environment for success, not just regulate it. This is a powerful lesson for other EU member states.

Roadblocks to revolution: barriers holding Europe back

If the potential of artificial intelligence is so great, why is the adoption rate not reaching 50% or more? The answer lies in a number of barriers that inhibit the wider and deeper integration of AI in the European economy. An analysis of these barriers shows that the biggest challenge is not the technology itself, but the human factor and the regulatory environment.

- The main barrier: lack of skills. In all the studies and reports, one factor comes to the fore as the biggest barrier: lack of appropriate skills and expertise. In one study from 2024, the importance of this factor increased in the perception of companies compared to the previous year, showing that the problem is growing. It’s not just about hiring data scientists; it’s about having employees who can identify AI use cases, manage implementation projects and work effectively with intelligent systems.

- Cost and complexity. The high cost of implementation and the complexity of the technology remain significant barriers, especially for SMEs. Failure rates of AI projects are high worldwide (estimated at 30-84%) and are often due to organisational, not just technological, issues.

- Data problems. Data availability and quality is another major obstacle. Many companies do not have the clean, structured and sufficiently large data sets necessary to train effective AI models.

- Legal and regulatory uncertainty. While the EU AI Act aims to provide a clear framework, it can also be a source of uncertainty in the short term. Concerns about legal implications, data protection and privacy are cited as significant barriers. Some voices criticise the EU regulatory approach for potentially stifling innovation compared to the more liberal approach in the US.

- Cultural resistance. A risk-averse culture and conservatism in the approach to business process change are cited as barriers more pronounced in Europe than in the US.

Europe finds itself in a strategic paradox. Its flagship policy, the AI Act, aims to build long-term trust, which is essential for sustainable technology adoption. Ensuring security and respect for fundamental rights should, in theory, increase trust among companies and the public.

However, in the short term, compliance burdens and legal ambiguities can act as a brake on innovation and adoption, especially for smaller companies that do not have extensive legal departments.

Companies point to ‘unclear regulations’ and ‘lack of clarity on legal implications’ as significant barriers. This contrasts with the more market-driven approach of the US, which encourages faster innovation but raises more ethical concerns.

So Europe is making a strategic choice: it is betting that a foundation of trust will ultimately lead to a more robust and human-centric AI ecosystem. The price for this, however, is lower speed and agility in the short term.

This is not an unequivocally good or bad approach, but it is a key strategic decision that helps to explain why Europe may appear to be ‘lagging behind’ in raw adoption rates while trying to lead the way in responsible implementation.

Separating hype from reality – the future of AI in European business

Analysis of the data on AI adoption in Europe leads to clear, albeit complex, conclusions. The picture that emerges is not a uniform march towards the future, but rather a patchwork of concentrated excellence, dynamic but shallow growth and vast, still untapped potential.

The leader is the region, not a single country. The true leader of AI adoption in Europe is not a single country, but a regional bloc including the Nordic countries and Benelux. Their success is based on a solid foundation of high digital maturity and proactive, ecosystem-focused national strategies.

Hype drives real but ‘shallow’ growth. The hype around generative AI is not empty; it has become a direct catalyst for a surge in adoption. However, this is largely ‘shallow’ adoption – focused on readily available language tools used in support functions such as marketing and administration. Deep, transformational integration of AI into key business processes in most companies is still lacking.

The reality is a two-speed Europe. The European AI landscape is defined by deep divisions: between the digitally advanced North and South and East; between large corporations and the SME sector; and between digital sectors and traditional industries. The benefits of the AI revolution currently accumulate in a small, elite segment of the European economy.

The main bottleneck is human. Europe’s biggest challenge is not access to technology, but a widespread shortage of AI skills and expertise. Overcoming this talent gap is the most important factor that can unlock wider adoption.