The European Union is entering a new phase of thinking about economic security. At a meeting of ministers in Denmark, which holds the rotating presidency, there was a proposal to impose additional conditions on Chinese investment in Europe – including the compulsory transfer of technology and know-how. This is a clear departure from the previous model of market openness and signals that Brussels is beginning to play by the rules that Beijing and Washington have been using for years.

Danish Foreign Minister Lars Rasmussen admitted that Europe had for too long assumed that adherence to free trade rules was enough in itself to win global competition. “If we invite Chinese investment to Europe, it must be linked to technology transfer,” he – he stressed. This phrase could become a turning point in EU industrial policy.

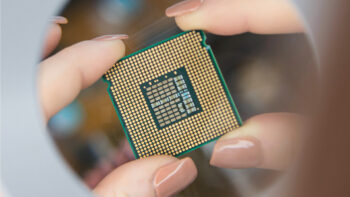

Brussels has been looking for months at how to mitigate the risks of capital inflows from authoritarian countries, particularly in strategic sectors – semiconductors, RES, critical infrastructure and electromobility. The European Commission is working on a document that is expected to present concrete tools by the end of the year: from screening investments to requiring ‘real investments’, as Trade Commissioner Maroš Šefčovič put it – those that create jobs, bring IP and transfer knowledge.

Beijing’s reaction was immediate. Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Lin Jian criticised the idea, speaking of “protectionist and discriminatory practices”. China officially opposes forced technology transfer – although European manufacturers of cars, industrial goods or wind turbines have indicated for years that such transfer was often a condition for entering the Chinese market.

Thus, in the background, there is a dispute over the definition of fairness in global trade. Europe, which for decades has relied on openness, is beginning to adopt a logic of reciprocity: access for access, technology for technology.

Is the EU ready for the policies it has criticised so far? And will European companies – especially those dependent on Chinese supply chains – support such a direction? The coming months will show whether Brussels manages to create common rules that balance competitiveness with security. One thing is certain: the era of naive free trade in Europe is about to come to an end.