For more than a decade, the Polish IT sector has been synonymous with uninterrupted, dynamic growth. It has established itself as the technological heart of Central and Eastern Europe, attracting global investment thanks to its huge talent pool and reputation as a reliable partner in nearshoring and outsourcing projects. The narrative of a ‘golden decade’ for Polish IT, driven by thousands of software houses and skilled developers valued worldwide, has become almost an axiom. However, in the past several months or so, this optimistic picture has begun to crack and the market has started to send deeply contradictory signals that have sown the seeds of uncertainty.

On the one hand, hard macroeconomic data paints a picture of a sector in peak form. The value of Polish IT services exports is breaking new records, demonstrating extraordinary strength and global competitiveness . Poland sells more IT services abroad than such technological powers as Japan or South Korea, which testifies to the maturity and sophistication of the solutions offered . On the other hand, there are increasingly loud signals from inside the industry about a cooling of the economy. Industry portals and labour market reports report a slowdown in recruitment, job cuts and a general sense of ‘adjustment’ after years of unbridled boom . This clash of two radically different narratives creates a fundamental paradox.

Are we witnessing the beginning of a stagnation that will end an era of spectacular growth? Or is this just a temporary breathlessness, a natural consequence of the global economic slowdown? Or, as seems most likely, are we seeing something much deeper – a fundamental process of market maturation and restructuring that is separating innovation leaders from companies basing their model on simpler services?

Market fundamentals: Between impressive scale and growing pressure

In order to understand the current state of the software house market, it is first necessary to look at its foundations – the number and structure of the companies that make it up. Registration data from the Central Statistical Office (CSO) and the Central Register and Information on Economic Activity (CEIDG) provide key information about the scale and dynamics of this ecosystem.

The analysis of the Polish IT sector is based on the Polish Classification of Activities (PKD), where the key role is played by Section J, Division 62: ‘Computer programming, consultancy and related activities’ . This category covers a wide range of activities, from code writing (PKD 62.01.Z), to IT consultancy (PKD 62.02.Z), to other information and computer technology services (PKD 62.09.Z). It is these subclasses that largely define the software house ecosystem in Poland.

Data from the REGON register, maintained by the Central Statistical Office, shows the impressive scale of the market . Industry reports estimate the number of technology companies in Poland at over 60,000, and between 500,000 and even 850,000 people work in the IT sector. This huge number of active entities testifies to the extraordinary density and vitality of the market. It is a landscape dominated by micro, small and medium-sized enterprises, which on the one hand testifies to the low barriers to entry and entrepreneurship, and on the other makes it more susceptible to economic fluctuations.

However, the sheer size of the market is only one side of the coin. The other, much more dynamic, is hidden in the CEIDG data, which records the fate of sole proprietorships (JDG) – a legal form extremely popular with contract programmers and small IT companies. An analysis of the number of deregistrations and business suspensions sheds light on the pressure this segment of the market has come under. The data from the last few years are clear and point to increasing pressure. In 2022, CEIDG received 9.6% more applications to close a sole proprietorship than the year before. In the first half of the other year analysed, the increase was even more dramatic at nearly 26% year-on-year. These figures are hard evidence that market conditions have become much more difficult for many smaller players.

The reasons for this phenomenon have to be sought in a combination of macroeconomic and regulatory factors. The global slowdown, high inflation, rising costs of doing business and changes in the legal and tax environment, such as the introduction of the Polish Deal, have hit the smallest entities in particular . However, these figures should be interpreted with caution. The high number of closures and suspensions in CEIDG is not only a symptom of the crisis. It also reflects the nature of the IT industry, which is dominated by project work. The CEIDG system is designed to make it easy to set up, suspend and close a business. For a contractor programmer, closing down a company can simply mean the end of one major project and moving to a contract of employment, and suspending a business is a common tool to manage liquidity in between assignments.

Global driving force: Exports as a barometer of success

While data from the domestic market point to increasing pressure, analysis of international trade paints a very different picture. The Polish IT sector has become a real export powerhouse in recent years, and the growth rate of foreign sales is a key argument against the stagnation thesis.

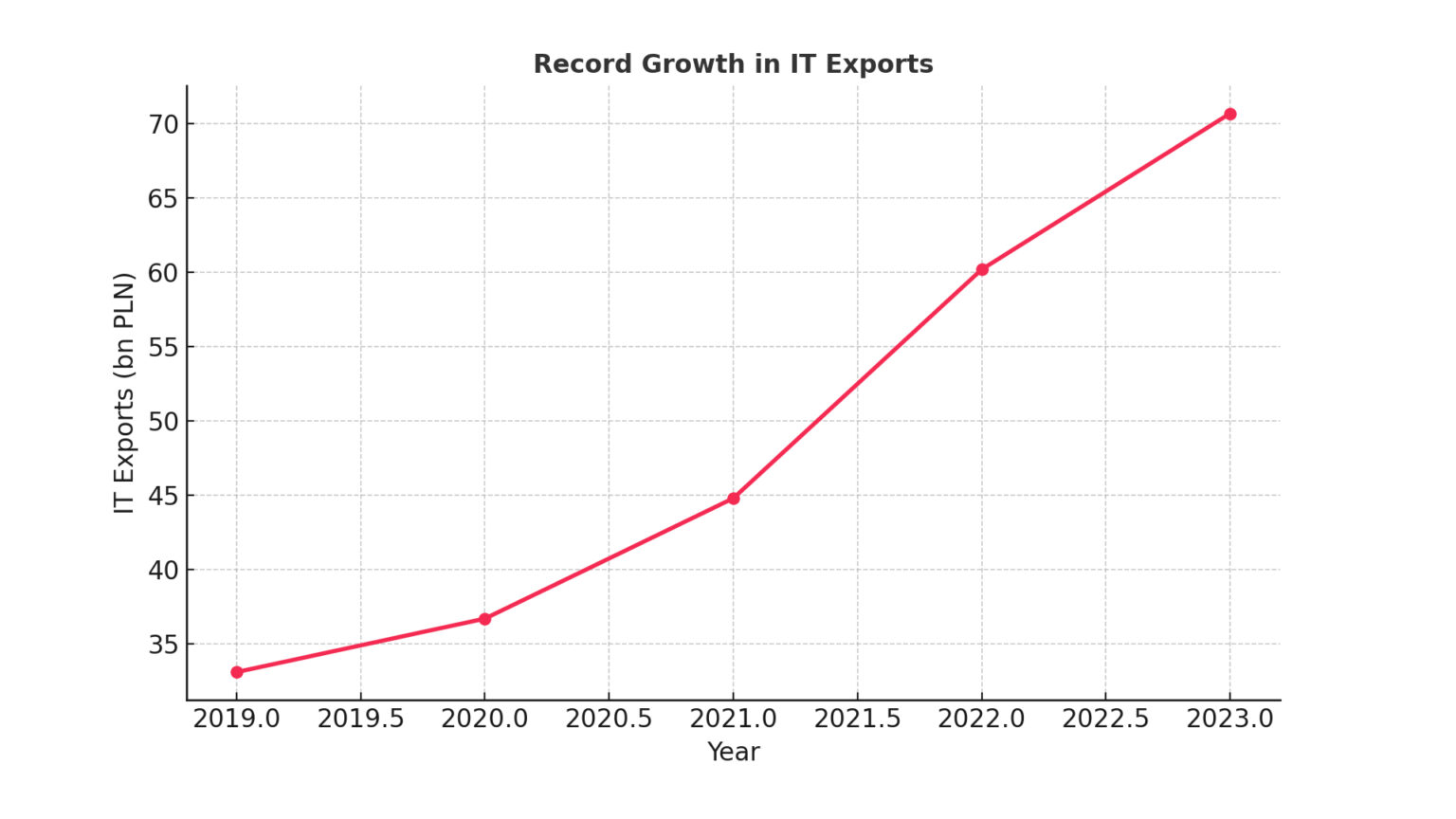

The figures speak for themselves. The value of Polish exports of services in the ‘telecommunications, IT and information’ category has increased from around PLN 33.1 billion in 2019 to more than PLN 70.7 billion in 2023 . This represents a more than doubling in just four years. Since 2010, exports of IT services have grown at an average annual rate of more than 20%, more than twice as fast as exports of all services in general . As a result, the share of IT services in total Polish services exports has increased from around 5% a decade ago to nearly 13% in 2022 .

According to data from the Polish Development Fund, based on Eurostat statistics, at the end of 2022 exports of IT services from Poland reached a value of EUR 11.66 billion, generating a significant trade surplus . Importantly, there has not been a single year of decline in this category since 2010, demonstrating the unrelenting demand for Polish digital competencies . This impressive trend fits into the wider European context. Eurostat data shows that telecommunications, computer and information services are one of the fastest-growing export categories for the European Union as a whole, with their share of total services exports (outside the EU) increasing by 7.2 percentage points between 2013 and 2023 .

This growth is not only quantitative, but above all qualitative. The Polish IT industry is breaking away from the image of a ‘digital assembly plant’, where the main competitive advantage was the lower price of software services. Increasingly, Polish companies are becoming strategic partners for global corporations, providing complex and technologically advanced solutions. Exported services are no longer just simple software development, but also advanced research and development (R&D) projects, strategic IT consulting, cloud services, cyber security and data analytics . This evolution is evidence of Poland moving up the global value chain. The main directions of this expansion are the world’s most demanding markets: the European Union countries (with Germany at the forefront), the United States, the United Kingdom and Switzerland.

Market reality: the end of the eldorado and a changing of the guard

The period when recruiters vied for every candidate and companies outdid each other in offering ever higher salaries is over. The last two years have seen a marked cooling and normalisation in the IT job market, which many observers describe as the ‘end of the eldorado’ . Reports from recruitment portals clearly indicate a shift in the balance of power.

The number of job offers published has fallen significantly compared to the peak years of 2021-2022 . At the same time, the number of applications per position has increased dramatically, with an average of 44 applications per offer in 2024, compared to 40 the year before . The most noticeable consequence of this change is the drastic reduction in opportunities for juniors. Companies, seeking to optimise costs and minimise risk, prefer to invest in experienced seniors who can deliver business value from day one . This turnaround in the market also comes at a human price – reports indicate increasing levels of stress, job burnout and feelings of job insecurity.

The cooling in the labour market is a direct consequence of the global economic downturn, which has forced software house clients to review their budgets . Inflation and economic uncertainty have prompted companies around the world to take a more cautious approach to technology investments . Customers, looking to save money, are freezing less critical projects and scrutinising every purchasing decision much more closely . For Polish software houses, this means longer sales cycles and the need to prove return on investment (ROI) at every step. The data from the SoDA report are telling here: small companies (up to 50 people) reduced an average of 26% of their IT specialists in the last year, while in large organisations (more than 300 people) this percentage was 12% . This shows that the market correction is hitting smaller, less stable players hardest.

New market requirements – Specialisation as the key to survival

The current market environment acts as a powerful evolutionary filter. In the boom times, demand was so high that almost every company, even those offering uncomplicated outsourcing of programmers (‘body leasing’), could count on orders. Today, the situation is radically different. The market places a premium on specialisation, deep domain knowledge and the ability to deliver complex, measurable business solutions.

Demand is shifting away from generalist programmers towards experts in niche but rapidly growing fields. An analysis of job vacancies shows that even with an overall decrease in the number of advertisements, areas such as Artificial Intelligence (AI/ML), Cyber Security, Data Analytics (Data & BI) and Cloud Engineering are still seeing increases in demand and offering high salaries . A company that today simply offers ‘Java developers’ is competing in a market that is becoming a commodity, susceptible to price pressure. By contrast, a company that provides ‘certified cyber security experts for the financial sector’ or ‘AI engineers with experience in logistics optimisation’ is selling a unique, high-margin solution.

This transformation is painful, but in the long term healthy for the sector as a whole. The market correction is not killing the industry, but accelerating its transition from a labour arbitrage-based model to one based on knowledge and innovation. This is a classic symptom of the industry’s transition from a phase of explosive growth to a phase of mature, more sustainable competition.

Not stagnation, but maturing through correction

Analysis of the data leads to a clear conclusion. What the Polish software house market is experiencing is not stagnation. It is a complex and multifaceted maturation process that is taking place through a profound, albeit painful, market correction.

Record exports and internal slowdown are not contradictory phenomena, but two sides of the same coin. Spectacular export success is being driven by leading players who have successfully moved to the next level of technological sophistication. The same process, however, raises the bar for the market as a whole. An internal adjustment, manifested by a slowdown in recruitment and pressure on smaller companies, is a natural consequence of this evolution.

The “golden decade” of easy, undifferentiated growth is irrevocably over. The future of the Polish IT sector will be shaped by new paradigms:

- Deep specialisation: Survival and growth will depend on the ability to build unique expertise in niche but strategically important areas. Companies must become experts in specific technologies (AI, cyber security, cloud) or industry verticals (fintech, healthtech, e-commerce).

- Business maturity: Skills in sales, marketing, financial management and strategy building will become crucial. Software houses need to evolve from technology workshops into mature, efficiently managed businesses .

- The AI revolution: artificial intelligence is becoming a fundamental tool to be integrated into your own processes to increase efficiency and reduce project delivery times. Companies that ignore this trend risk losing their competitiveness .

Although the current period is challenging, the outlook for the Polish IT sector remains optimistic. As it goes through this transformation, the industry is becoming stronger, more diverse and resilient to shocks. The adjustment, although painful, is a necessary stage in the evolution that is transforming the Polish IT sector from a regional talent basin into a mature global technology leader capable of competing at the highest global level .