The Polish artificial intelligence scene in 2025 is a tale of two extremes. On the one hand, we are witnessing unprecedented successes. Polish AI startups such as ElevenLabs are raising hundreds of millions of zlotys from the world’s leading investors, and the country is actively participating in the global technology race by developing advanced concepts such as agent-based AI. On the other hand, hard data paints a picture of a deep crisis in the domestic market: the largest skills gap in 15 years, alarmingly low maturity of implementations in companies and a lack of a strategic approach to talent development.

This discrepancy – let’s call it the Polish AI paradox – is not just a statistical curiosity. It is a fundamental strategic challenge. If it is not resolved, Poland risks consolidating its position as a nation of skilled users of off-the-shelf AI tools instead of becoming a nation of foundational technology developers. In the long term, this undermines our competitiveness and risks squandering the historic opportunity presented by the AI revolution.

Poland as an exporter of innovation

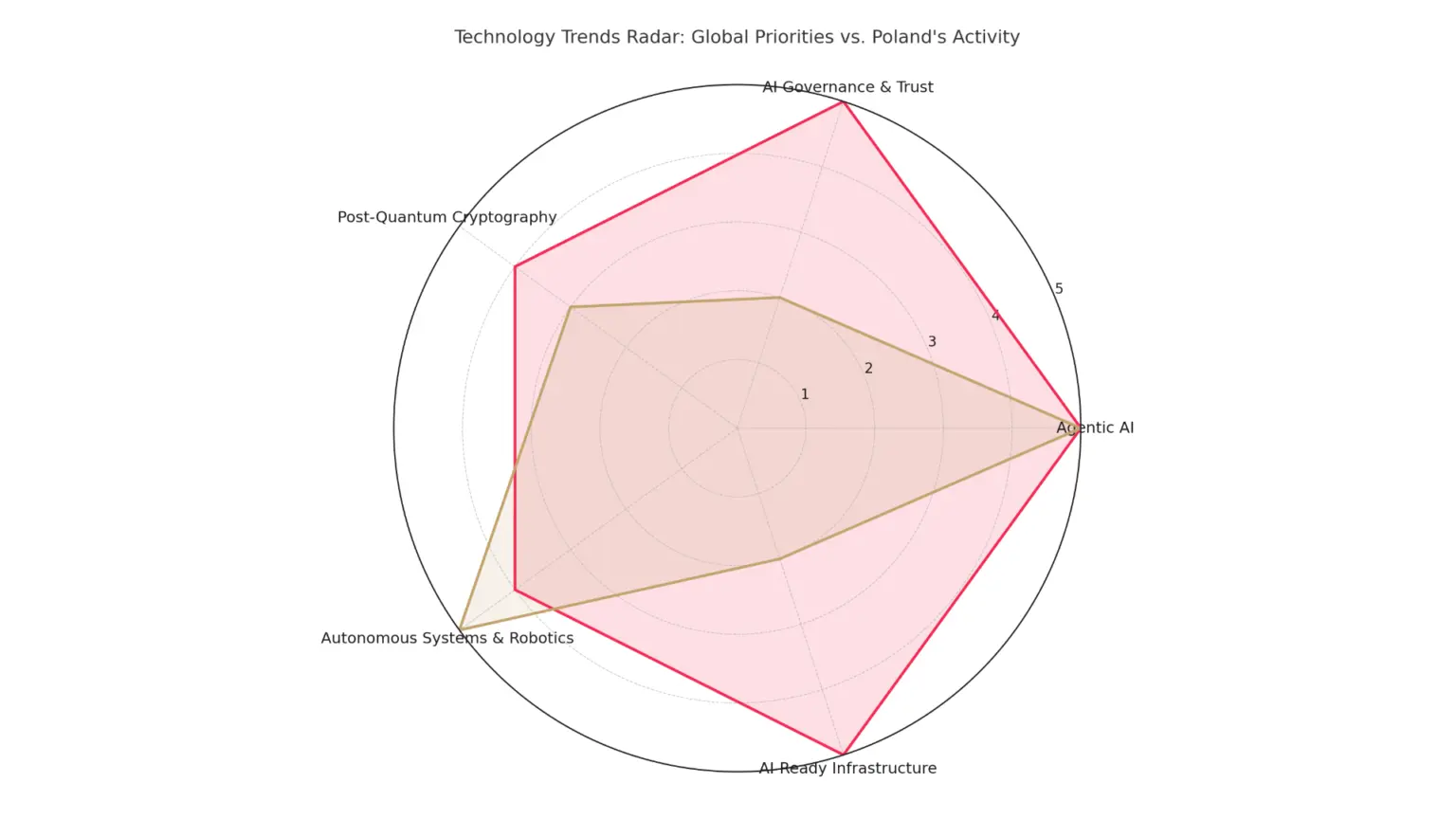

There is no doubt that the Polish technology sector is fully integrated into the global circulation of ideas. Key trends for 2025, identified by leading analyst firms such as Gartner and Forrester – including agentic AI (Agentic AI), governance AI (AI Governance) or reasoning AI (Reasoning AI) – are not only being discussed, but actively developed in Polish companies.

More importantly, these ambitions are translating into tangible, financial successes. In 2024, Polish startups related to artificial intelligence have attracted more than PLN 1 billion in venture capital. Spectacular funding rounds, such as the raising of over PLN 700 million by ElevenLabs or PLN 121 million by Wordware, prove that Polish companies are able to compete at the highest global level and attract capital from the most prestigious funds, such as Andreessen Horowitz. These successes reinforce investors’ belief that Poland has real potential to become a major AI hub in the CEE region.

Crisis of competence and adoption

However, when we look at the internal market, optimism gives way to concern. The demand for AI talent has created the largest skills gap in Polish IT in over 15 years. The shortage of specialists has increased by an alarming 82% in one year. This crisis is being felt at board level. According to the Microsoft Work Trend Index report, as many as 84% of Polish business leaders plan to deploy AI agents, but at the same time admit that there is a deep ‘competency gap’ in their organisations.

This gap between ambition and action is striking. Despite declarations to the contrary, as many as 52% of organisations do not provide any generative AI training to their teams. The implementations that do take place are often superficial. According to McKinsey data, only 1% of managers in Poland describe the implementation of AI in their organisation as “mature”. Although 78% of respondents declared the use of this technology in 2024, it seems to be mainly experimental and not deeply integrated into the company’s strategy.

Systemic response and strategic trap

The Polish educational system and market have responded to these challenges. Leading universities such as Jagiellonian University, Warsaw University of Technology and Poznan University of Technology already offer specialised degrees and postgraduate programmes in artificial intelligence. These activities are complemented by private sector initiatives, such as Microsoft’s programme to train one million Poles, and government strategies to develop digital competences.

Nonetheless, we are facing a fundamental challenge that concerns the quality, not just the quantity, of these competences. We are seeing an explosive growth in a phenomenon that can be called ‘AI Literacy’ (AI) – that is, the ability to use off-the-shelf tools. Seven out of ten Poles use AI regularly, often without formal training or employer knowledge. Furthermore, 44% of employees prefer to delegate tasks to AI rather than a human colleague, valuing its accessibility and speed.

However, this is evidence of a growing ability to consume technology rather than create it. The real long-term economic value and competitive advantage lies in something else – in ‘AI fluency’ (AI Fluency), i.e. the ability to build, integrate and modify complex AI-based systems.

ElevenLabs’ success came not from the skilful use of other people’s models, but from the creation of its own ground-breaking technology solution. It was this ability to create fundamental intellectual property that attracted global capital. If the Polish economy is to fully capitalise on its ambitions, we need to make a strategic turnaround.

From user to creator

The Polish AI paradox puts us at a crossroads. We can follow the path of mass adoption of off-the-shelf tools, becoming an efficient but still dependent market on external suppliers. This is a safe path, but one that limits our potential to a subcontractor role in the global AI value chain.

The alternative is to consciously and strategically build competence in technology creation. This requires a fundamental shift in thinking – both at the level of state strategy, corporate programmes and curricula. We need to aggressively shift the focus from teaching how to use AI to training engineering and scientific talent capable of building with AI.

It is necessary to support not only startups, but the entire ecosystem that creates them: from basic education, to specialised studies, to incentives for R&D in Poland. Companies need to stop seeing AI training as a cost and start treating it as a key investment in building competitive advantage.

Solving the Polish AI paradox will determine our economic position for decades. We have global talent and ambition. Now we need to build a domestic foundation that allows them to fully flourish. It is time to move from fascination with the possibilities of AI to strategically building our own capabilities in this field.