Set up in minutes from your smartphone, without a single paper document. Access to all medical records in a few clicks. Settling taxes thanks to forms that the administration has filled out for us.

This is not a vision of the future, but an everyday reality in the digital vanguard of the European Union. At the same time, in other member states, the same processes can still be a multi-stage, bureaucratic ordeal. This contrast perfectly illustrates the revolution that is the digitalisation of public services – a fundamental change in the relationship between the state, the citizen and the entrepreneur.

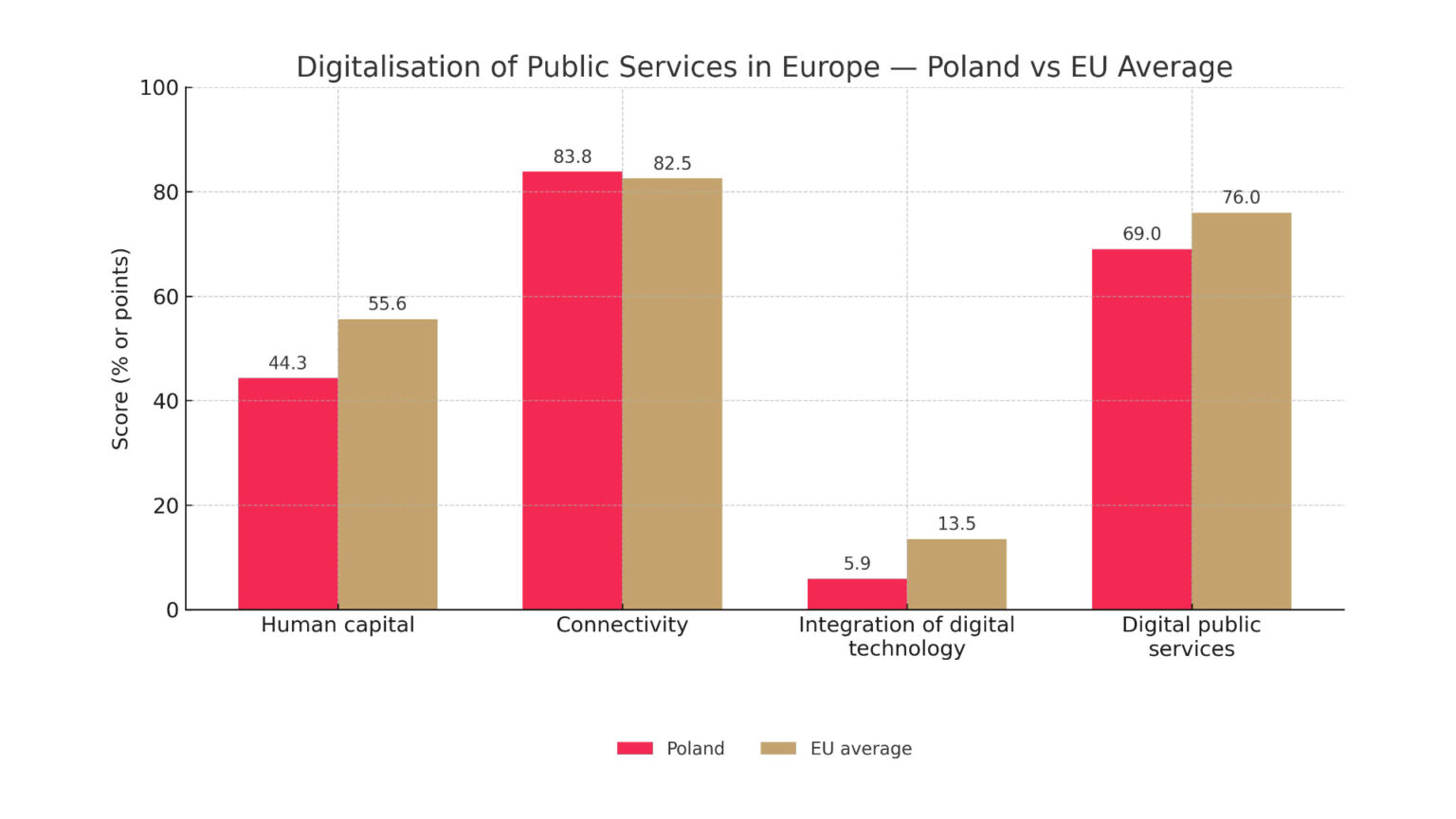

To measure progress in this transformation, the European Commission has been publishing the Digital Economy and Society Index(DESI) since 2014. It is a key analytical tool that assesses countries in four areas: human capital, connectivity, digital integration and digital public services.

From 2023, the DESI indicators became part of the Road to the Digital Decade programme, setting ambitious 2030 targets for the entire Union, such as 100% availability of key public services online.

Analysis of DESI data paints a picture of a two-speed Europe. On the one hand, we have a group of leaders who are setting global standards, on the other, a peloton of countries still catching up. Poland occupies a fascinating and contradictory position in this landscape – a country that impresses in some aspects of e-government and lags far behind in others.

EU leaders: anatomy of a digital success story

The same group of countries has been at the top of the European digitalisation rankings for years: the Scandinavian countries (Finland, Denmark), the Benelux countries (Netherlands, Luxembourg) and an absolute phenomenon in this field – Estonia. Countries such as Malta and Spain have also joined the top, having made a huge leap in quality in recent years.

Their success is not a coincidence, but the result of a coherent, long-term strategy based on several pillars.

Firstly, long-term vision and political will. In these countries, digitalisation is a strategic state priority, pursued regardless of changes in the political scene.

Secondly, strategic investment. Leaders not only allocate sizable resources, but also make effective use of EU funds such as the Reconstruction and Resilience Facility (RRF).

Third, a solid foundation. A high level of e-services is inextricably linked to the digital competence of the population and universal access to ultrafast internet – areas in which the Nordic countries are world leaders.

The most important factor, however, is the culture of trust. Citizens in Scandinavian countries or Estonia trust the state to process their data securely and transparently. This trust is the currency that enables the implementation of advanced services such as digital identity (eID) or centralised medical e-documentation.

These elements create a ‘flywheel effect’. The successful implementation of one key service builds trust and gets citizens used to interacting with the state online. This, in turn, creates demand for further and more advanced solutions, driving further development.

In this way, the leaders not only maintain their lead, but actually increase it, making it extremely difficult for the rest of the stakes to catch up with them.

To understand how this works in practice, just look at some examples:

- Estonia is a global model of a ‘digital nation’, where 99% of public services are available online. The backbone of the system is X-Road, a secure data exchange platform that implements the “once-only” principle. – a citizen only provides their data to the administration once. Every Estonian has a digital identity card (e-ID) that allows for a legally binding signature, saving everyone an average of five working days per year. The country has even gone a step further by creating e-Residency, a programme that allows entrepreneurs from all over the world to set up and run a company remotely in the EU.

- Denmark is a champion of user-centred service design. Instead of forcing citizens to navigate a complex structure of offices, Denmark has consolidated services into portals based on ‘life events’. Borger.dk is a one-stop shop for citizens to deal with almost any issue, from taxes to enrolling a child in school, and virk.dk is its counterpart for business.

- Finland and the Netherlands are examples of pragmatism and innovation. Finland is developing proactive services based on artificial intelligence (AuroraAI programme) to anticipate citizens’ needs at key moments in their lives. The strength of the Netherlands, on the other hand, is its extremely solid foundations – the highest digital competence rates of the population in the EU and the excellent infrastructure on which the entire ecosystem of services centred around the DigiDdigital identity is based.

The Polish paradox: the leader at the back of the pack

An analysis of Poland’s position on the digital map of Europe leads to surprising conclusions. In the overall DESI 2022 ranking, Poland ranks at the bottom, taking 24th place out of 27 countries. Our performance in key areas, such as human capital or the integration of digital technologies by companies, is well below the EU average.

However, there is one bright spot in this bleak picture: digital public services. In this category, Poland not only performs relatively best, but shows one of the highest rates of improvement in the entire EU. In several key indicators, we have even surpassed the European average:

- Pre-filled forms: as many as 78% of online forms in the Polish administration are pre-filled with data that the state already has (EU average: 68%).

- Access to medical e-documentation: Thanks to systems such as the Internet Patient Account (IKP), 86% of Poles have access to their medical data online (EU average: 72%).

These successes are the fruit of the development of platforms such as the gov.pl portal, the mObywatel application or the ZUS Electronic Services Platform. However, behind this impressive facade lies a deeper problem. Despite the fact that we are creating advanced services that are well rated in benchmarks, their actual use by citizens is alarmingly low.

Only 37% of Poles use e-government, while the average in 16 EU countries exceeds 50% and in Denmark it reaches 73%.

So we face the risk of a digital ‘Potemkin village’. We have built state-of-the-art e-services that perform brilliantly in technical audits, but they stand on weak foundations – some of the lowest digital literacy rates of the population in the EU. There is a deep gap between accessibility and service adoption. It is this gap that is the biggest challenge for Poland’s digital transformation.

Strategy 2035: a plan for a digital leap

In October 2024, the Polish government presented the draft “Digitisation Strategy of Poland until 2035”. – a document that attempts to provide a comprehensive response to the challenges described above. Its ambitions are revolutionary. By 2035, 100% of official matters are to be handled digitally, 20 million Poles are to have a digital identity wallet in the mCitizen application, and the number of ICT specialists is to increase to 1.5 million. PLN 100 billion is to be allocated to realise these goals by 2030.

More importantly, however, the strategy is holistic. It explicitly states the need to end ‘silos’ in government and combines the development of e-services with powerful investments in the foundations: digital competences (target: 85% of citizens with basic skills), infrastructure and cyber-security.

This demonstrates the understanding that it is impossible to achieve sustainable success by building more applications without parallel work on the skills and trust of citizens.

“Strategy 2035” should be seen as an attempt to “set off its own flywheel”. It is a plan for rapid acceleration, which should make it possible not only to catch up, but to realistically close the development gap separating us from European leaders.

From technology to people

Europe’s digital transformation is a process that exposes deeper gaps in social capital, trust and long-term planning. Poland, despite impressive progress in the creation of e-services, is still struggling with a fundamental challenge: how to make advanced tools widely used and accessible to all.

The new digitalisation strategy makes the right diagnosis, shifting the focus from the technology itself to building competence and an integrated ecosystem. Its success will depend on consistency in implementation.

For the true measure of success will not be the number of new applications, but the percentage of citizens who can use them consciously, safely and effectively. The road from a ‘Potemkin village’ to a fully digital nation is not a technological sprint, but an educational and social marathon.