In the business narrative, the technology industry is synonymous with youth, dynamism and a constant influx of new talent. The common perception of the IT sector as the domain of people under 30 is so strong that the question of its ageing sounds almost like heresy. However, the latest Eurostat data sheds a whole new light on this picture, revealing a fundamental paradox that has direct implications for Polish companies, especially in the SME sector.

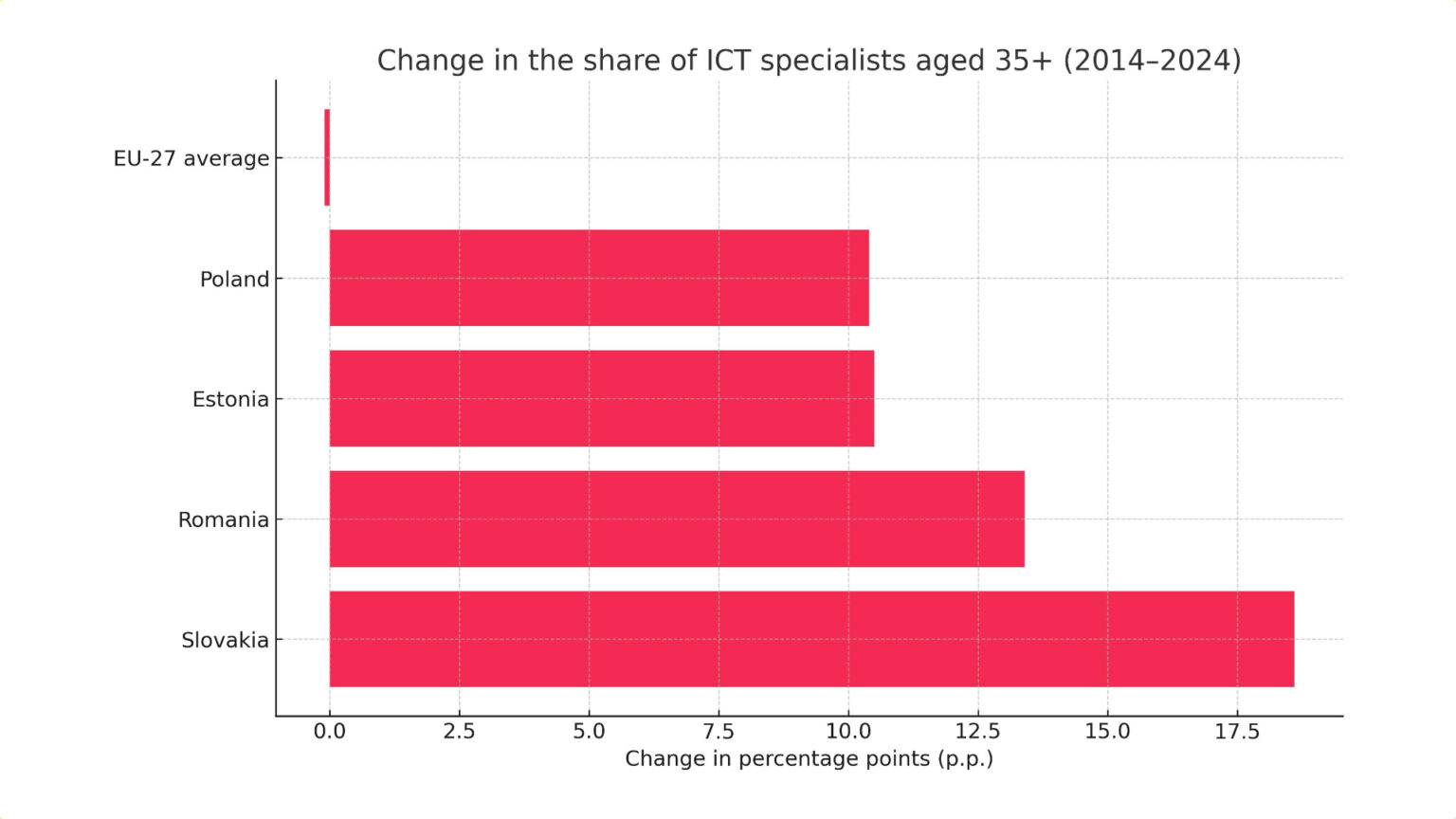

Analysis of data from the last decade (2014-2024) brings a surprising conclusion: the European IT sector as a whole is not ageing at all. On the contrary, it shows remarkable demographic stability. In 2024, the share of ICT (information and communication technology) professionals aged 35 and over across the European Union was 62.8%. A decade earlier, the figure was marginally higher at 62.9%. However, this almost zero change (-0.1 percentage points) is not a sign of stagnation, but of a dynamic equilibrium.

This stability is the result of two powerful forces clashing. On the one hand, the ICT industry is growing at a rate unmatched by the rest of the economy. Between 2014 and 2024, the number of ICT professionals employed in the EU increased by as much as 62.2%, while total employment in the EU grew by only 10.6%. Such massive growth generates a constant demand for new staff, met mainly by graduates, which naturally rejuvenates the sector. On the other hand, the powerful base of professionals hired a decade or two ago is naturally maturing, moving into older age groups. At an EU-wide level, these two trends are almost perfectly balanced. The IT sector in Europe is therefore a mature market – where almost two-thirds of the workforce is over 35 – but thanks to expansion, as a whole, it is not ageing.

However, this pan-European balance masks ‘contrasting national trends’, and Poland is one of the clearest examples of this divergence. While the share of ICT professionals aged 35+ declined in the EU, in Poland it increased by as much as 10.4 percentage points over the same period. This places Poland among the top countries with the fastest maturing technology workforce, alongside Slovakia (+18.6 p.p.) or Romania (+13.4 p.p.).

This does not mean that the Polish sector is ‘old’, but that it is maturing at a rapid pace. There are several factors behind this phenomenon. Firstly, it is the effect of the maturing of the market. The generations that fed into the industry en masse during the recruitment boom of the 2000s and 2010s are now collectively crossing the threshold of 35 and 45 years of age. Secondly, this trend is reinforced by the overall unfavourable demographic situation in the country. Poland is an ageing society at a rapid pace , which translates into a shrinking pool of young talent across the labour market. Finally, the market itself has started to favour experience – the observed slowdown in the recruitment of juniors goes hand in hand with a growing demand for experts, including in the context of the development of AI.

As a result, the Polish IT sector is losing its former ‘youth’ advantage. The age structure of the industry, visualised in the form of a pyramid, would show a clear ‘convexity’ in the 25-34 and 35-44 age cohorts, which contrasts with the much older and flatter structure of the total workforce in the Polish economy.

For Polish SME companies, this rapid demographic shift creates a fundamental conflict: a clash between cultural stereotypes and market reality. The organisational culture of many technology companies, both globally and in Poland, is steeped in ageism, or age discrimination. Stereotypes perceiving older workers as “less adaptable” or “unwilling to learn” are still common. Polish studies show glaring disparities: candidates aged 28 receive twice as many invitations to interviews as people over 50, with identical qualifications.

With demographics forcing a reliance on older staff, this cultural ageism is becoming a strategic mistake. Companies that continue to use platitudes about a ‘young, dynamic team’ in their recruitment communications , are actively scaring away the largest and most experienced talent pool in the market. In an era when more than half of EU businesses report difficulty filling ICT vacancies , this is a business barrier that raises recruitment costs and increases turnover.

Adapting to this new reality requires SMEs to immediately revise their strategy. Competing for a growing pool of experienced experts cannot be based on salary alone. It becomes necessary to implement conscious Age Management strategies. This means focusing on critical areas for a mature workforce. Firstly, on the strategic transfer of knowledge. Experienced specialists (50+) are often the “first generation” of Polish IT, possessing invaluable knowledge of key systems. Their departure without a succession plan, e.g. through mentoring or workshops, means an irrevocable loss of critical ‘know-how’. Secondly, SMEs can gain an advantage by offering values valued by seniors: employment stability , real flexibility and attention to work-life balance.

Redefining development and upskilling is becoming equally important. Investing in the development of a senior looks different to that of a junior. It is no longer just about learning a new framework, but about developing competences that multiply the value of their experience. Companies need to create formal technical development paths (e.g. Staff/Principal Engineer) that allow for promotion and salary increases without moving to a managerial path. This is a development towards technical leadership , systems architecture and taking full responsibility for a product area.

Finally, this internal strategy must be reflected in the company’s external communication, i.e. in its Employer Branding. It is time to audit recruitment language and eliminate ageist language from it. Instead, communications should consciously showcase and celebrate experienced employees as mentors and innovation leaders.

The question “is the IT industry ageing?” has a complex answer: in Europe – no, in Poland – yes, and rapidly. The Polish IT sector has ceased to be a “young industry” and has become a mature market. The competitiveness of SMEs in the coming decade will not depend on the ability to attract the youngest, but on the ability to strategically retain, effectively develop and fully utilise the potential of the growing number of professionals over 35. The greatest competitive advantage will be gained by those companies that are the first to abandon stereotypes and adapt their culture to the demographic reality.