The debate about the impact of artificial intelligence on the labour market is dominated by visions of mass redundancies. However, the latest data from the US market paints a very different and much more worrying picture.

The real threat to entry-level professionals is not layoff notices, but a silent and invisible barrier – the drastic reduction in recruitment for junior positions. Companies that implement AI are not cleaning up their ranks. They are closing the gates to new recruits, creating a ticking bomb that will threaten the talent market for years to come.

Quiet revolution: Less recruitment, not more redundancies

The narrative of robots taking jobs is a media buzzword, but data shows that the reality is more complex. An analysis of nearly 285,000 US companies reveals that organisations actively implementing generative AI are following the path of least resistance.

Instead of carrying out costly and image-damaging redundancies, they are simply cutting back on hiring new people at the lowest levels.

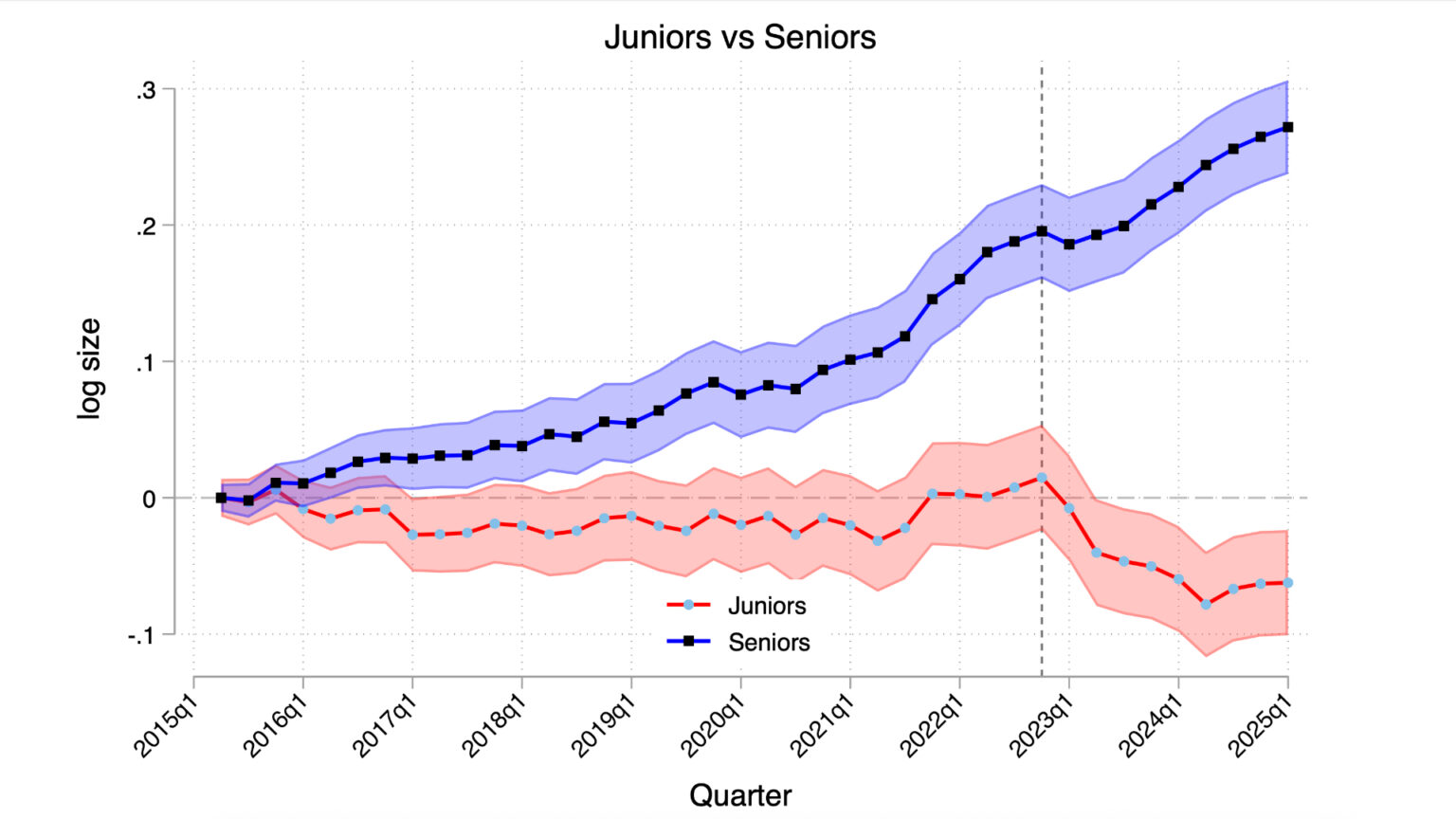

The figures are unequivocal. Since the first quarter of 2023, when generative AI became widespread, companies implementing these technologies have seen a 7.7% drop in junior positions compared to companies that do not.

Crucially, this decline is almost entirely driven by a slowdown in recruitment. AI ‘adopter’ companies hired an average of 3.7 fewer juniors per quarter after Q1 2023 compared to companies not investing in AI.

What’s more, the departure rate (redundancy and natural turnover) of juniors in the same companies not only did not increase, but actually decreased slightly.

Companies are therefore not getting rid of current juniors. They simply stop hiring new ones to replace them or fill vacancies. It’s a quiet, ‘invisible’ cutback that doesn’t generate headlines, but over the course of a few years it could dry up the source from which the market draws experienced professionals.

Why is AI targeting the lowest rung of the ladder?

To understand this mechanism, it is necessary to look at the nature of junior jobs. Careers in many white-collar jobs start with tasks that researchers describe as ‘intellectually mundane’ – routine but cognitively demanding.

Examples include debugging code, reviewing legal documents, creating standard reports or responding to repetitive customer queries.

It is these tasks – structured, pattern-based and information processing-intensive – that are the ideal target for the current generation of AI. Large language models excel at analysing and generating text, finding errors in code or conducting structured conversation.

In effect, artificial intelligence does not replace the employee as a whole, but automates the core of their daily duties.

The problem is that these ‘mundane’ tasks were never an end in themselves. They were a fundamental mechanism for learning and gaining experience. It is through debugging hundreds of code snippets that a young programmer acquires intuition and learns good practice.

By automating these processes, companies are unknowingly automating their own talent development system, which raises a fundamental question: will a manager who has never performed the core tasks be able to effectively manage a team that does, even if with the help of AI?

Unequal impact: Who loses the most?

The wave of change brought about by AI is not hitting everyone with equal force. Sectoral and educational analysis shows that there are groups that are particularly vulnerable.

The largest, almost 40 per cent, decrease in the employment of juniors was in the wholesale and retail sector. Tasks such as routine communication with customers, handling enquiries and processing paperwork were found to be highly susceptible to automation.

Significantly, finance, manufacturing and professional services also suffered significant declines, confirming that this is not a phenomenon limited to the technology industry.

Even more surprising are the findings regarding education. The study revealed a clear U-shaped pattern. It turns out that graduates from good but not elite universities (defined as Tier 2 and 3) are the most likely to reduce recruitment.

Smaller declines affected graduates from universities at the very top (Tier 1) and, interestingly, those at the lower tiers (Tier 4 and 5).

The logic behind this phenomenon is purely economic. Graduates from the elite are protected by their unique creativity, which is difficult to automate, and their high salaries are a justifiable investment anyway. In contrast, entry-level employees are protected by their low cost – implementing AI can be more expensive than their labour.

In the ‘death zone’ were graduates from the middle – expensive enough to make their automation viable, yet performing tasks structured enough that AI can handle them well.

Fortress of talent: Fewer doors, but a faster lift upwards

However, the analysis also brings a glimmer of hope, at least for those already in the system. It turns out that companies implementing AI, while closing their doors to newcomers, are at the same time taking more care of existing employees. In these companies, the rate of promotions awarded to juniors has increased.

This can be interpreted in two ways.

Firstly, AI, which replaces the tasks of beginners, simultaneously becomes a ‘force multiplier’ for more experienced juniors, allowing them to focus on more complex problems and advance faster.

Secondly, if a company is reducing external recruitment, it needs to rely more on an internal source of talent to fill senior vacancies.

This creates a new dynamic of the ‘talent fortress’. Companies are raising the walls, making it more difficult to enter from the outside, but investing more heavily in developing those already inside.

A clear divide is emerging between ‘insiders’, who have found themselves on an accelerated career path, and ‘outsiders’ – graduates for whom the barrier to entry is getting higher.

Strategic challenge: Where will we get our seniors from in five years’ time?

The figures presented lead to one fundamental question that should keep business leaders and HR departments awake at night: where will we get experienced professionals from in five years’ time if we cut off the supply of ‘fresh blood’ today?

This is not a rhetorical question. It is a strategic challenge that requires a fundamental rethink of existing talent management models. The crisis in the market for experienced professionals, which will hit with full force at the end of this decade, is being created here and now.

Decisions not to recruit juniors, taken en masse between 2023 and 2025, will directly translate into an acute shortage of qualified professionals with 3-5 years’ experience between 2028 and 2030.

One can predict with a high degree of probability what will happen next. There will be a ‘missing generation’ of professionals on the market. The huge imbalance between supply and demand will trigger an unprecedented war for talent and a hyperinflation of salaries for the few who will have the desired experience.

Companies that today, in the name of short-term optimisation, forgo investment in their talent pipeline will face a dramatic choice in a few years’ time: either they pay a gigantic premium for experienced employees or they will not be able to meet their business goals.

This is the ultimate deferred cost of the ‘invisible cuts’ that are taking place before our eyes.