Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) has long ceased to be seen as an ’emerging’ technology market. Today, it is a globally established, dynamic and competitive centre of innovation, whose IT services and R&D market is growing four to five times faster than the global average.

At the heart of this technological renaissance are four key players, a kind of ‘Visegrad+ Technology’: Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Romania. Each of these countries brings a unique profile to the regional jigsaw: Poland appears as a regional hegemon in terms of scale, the Czech Republic as a stable industrial and technological centre, Hungary as a magnet for foreign direct investment and specialised expertise, and Romania as a ‘digital contender’ with the highest growth rate.

CEE technology arena

To understand the dynamics of competition in the region, it is first necessary to assess the fundamental economic context, comparing the scale, structure and importance of IT markets in each of the four countries. It is these indicators that determine who are the biggest players and where the epicentre of growth lies.

Scale and dynamics of the market: measuring the forces

Market size is a fundamental indicator of strength. In this respect, Poland is the undisputed leader in the region, although different sources give slightly different estimates, reflecting the complexity and dynamics of the sector. According to PMR data, the value of the Polish IT market in 2023 was PLN 66.3 billion (approx. EUR 15.4 billion), with a forecast of growth to PLN 74 billion (approx. EUR 17.2 billion) by 2025. IDC Poland analysts, on the other hand, estimate this value even higher – at PLN 80.3 billion (approx. EUR 18.6 billion) in 2023. Regardless of the methodology adopted, the scale of the Polish market significantly exceeds its neighbours.

The Czech ICT (information and communication technology) market presents the picture of a mature and stable powerhouse. Its revenues are forecast to reach EUR 24.3 billion by 2026, with a steady annual growth rate of 2.1%. This indicates a less volatile, well-established market. The Hungarian ICT market is more difficult to assess conclusively due to disparate data. Mordor Intelligence estimates its value at an impressive USD 35.17 billion in 2025, with a projected annual growth rate (CAGR) of 11.41% until 2030. Other sources quote a more conservative figure of €5bn for 2024. This discrepancy suggests that the higher estimate covers a wide range of telecoms services and hardware sales, driven by large corporations. The Hungarian e-commerce segment alone reached HUF 1,920 billion (approximately EUR 4.9 billion) in 2024.

Romania presents the most dynamic picture. Its digital economy is expected to reach a value of EUR 52 billion by 2030. The IT services export market, valued at EUR 24.9 billion in 2023, is expected to grow to EUR 44.8 billion by 2028, representing an impressive CAGR of 9.1%. This is the fastest growth trajectory in the group analysed, positioning Romania as a top contender for regional momentum.

This dichotomy between scale and speed of growth creates a strategic tension. Poland, as the largest market, offers stability, a mature and diverse ecosystem, which is attractive to large corporations looking for space for R&D centres. On the other hand, Romania, with its near double-digit growth, is a magnet for venture capital funds and companies looking for rapid expansion, willing to accept the risks associated with a less mature market. The choice between these countries is therefore not a simple decision, but depends on the investor’s appetite for risk and its growth strategy.

The powerhouse that drives GDP: More than the service sector

The importance of the IT sector for national economies is best reflected in its share of Gross Domestic Product. In Poland, it is an impressive 8%, reflecting the deep integration of technology into the overall economy and its key role as a driving force. Romania also boasts a high figure at 6.6%. Surprisingly, Hungary has the lowest share at 4.3%. Although precise data for the Czech Republic is lacking for IT alone, the context is the powerful automotive industry, generating 10% of GDP, indicating strong links between the technology sector and industry.

These figures, juxtaposed with overall wealth levels, show that technology is a key tool for convergence. Poland and Romania, with GDP per capita (in purchasing power parity) at 79% of the EU average, are chasing the Czech Republic (92%). The IT sector is undoubtedly one of the main accelerators of this process.

Market Architecture: What’s hiding under the hood?

The internal structure of the IT markets in each country reveals their unique specialisations and strategic directions.

Poland: We are seeing a clear bifurcation of the market. The hardware segment is stabilising after a pandemic boom, while software and services are going from strength to strength, reaching a value of PLN 30.5bn (€7.1bn) in 2023. Cloud services are a key driver, with the market growing by 25% year-on-year to reach US$2bn.

Czech Republic: The market is strongly determined by a powerful industrial base, especially the automotive and electrical engineering sectors. This generates a huge demand for embedded systems, industrial automation and advanced enterprise IT solutions. The country is also a hub for international R&D centres such as Microsoft, IBM and Oracle.

Hungary: the market is characterised by an exceptionally high level of high-tech adoption by businesses. The cloud adoption rate is 37.1% (slightly below the EU average) and data analytics as high as 53.2%, which is well above the EU average (33.2%). This indicates a mature and demanding corporate customer base. The largest segment of the ICT market is telecommunications services, accounting for more than 41% of the total.

Romania: the market is largely export-oriented, especially in the area of software development services. Despite the government’s strong emphasis on the digitalisation of small and medium-sized enterprises, its level (27%) still lags far behind the EU average (57.7%), which paradoxically creates a huge potential for growth in the internal market.

An analysis of the structure of markets reveals an interesting phenomenon in Hungary. On the one hand, companies there show above-average maturity in the adoption of advanced technologies such as data analytics.

On the other hand, the contribution of the overall IT sector to GDP is the lowest in the group. This apparent contradiction suggests that technological advancement is concentrated in a narrow group of large, often foreign corporations (e.g. from the automotive sector), rather than being a widespread phenomenon driven by a broad domestic IT industry.

This indicates a ‘top-heavy’ market with potentially fewer opportunities for local SMEs compared to Poland, where the domestic IT sector is a much larger economic force.

The human capital equation: talent, skills and remuneration

In an industry dominated by a ‘war for talent’, it is human capital that is the most valuable asset and the ultimate determinant of competitiveness. The analysis moves from macroeconomic numbers to the practical realities of building and maintaining technology teams.

Talent resource: A deep but challenging resource

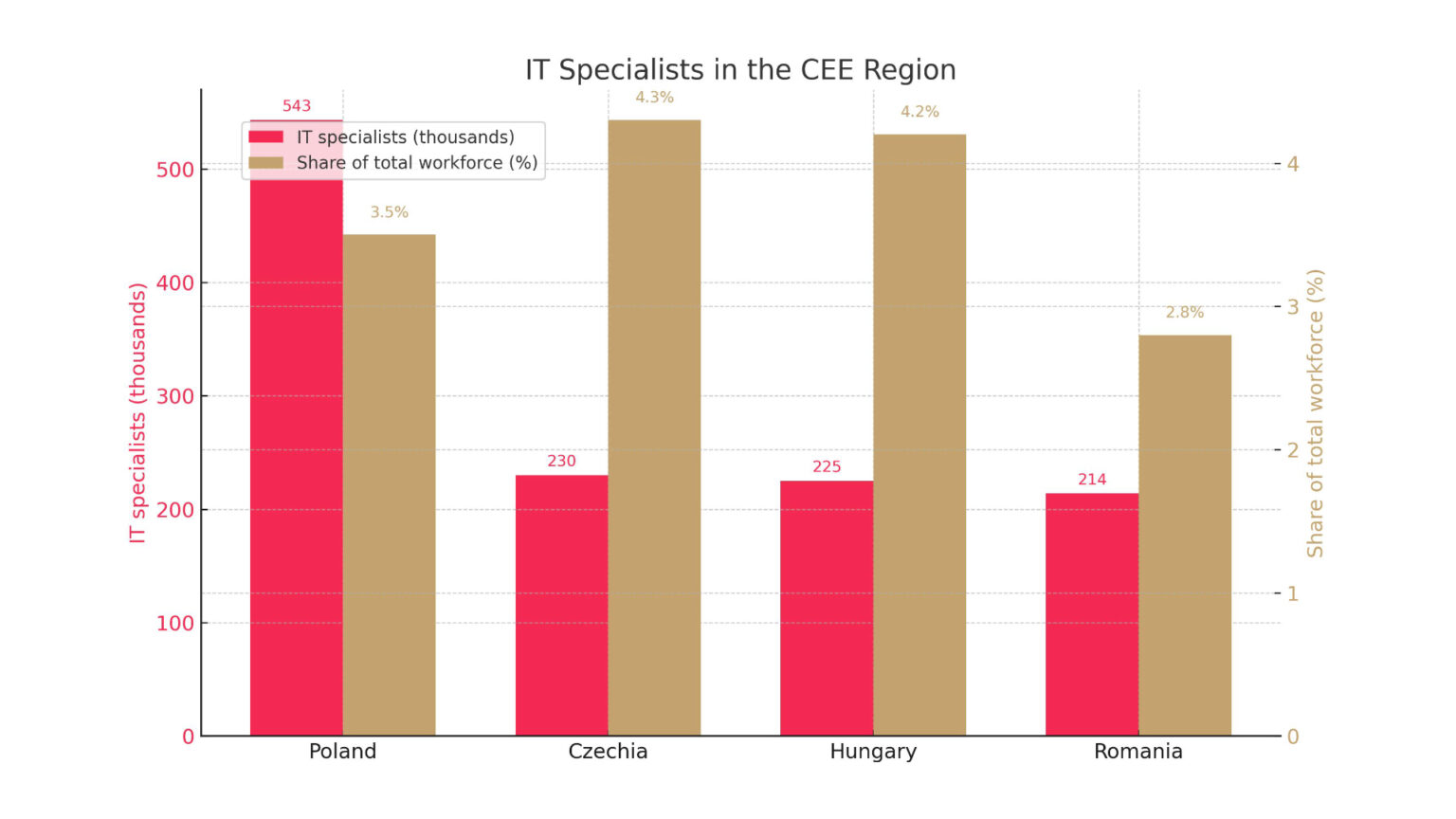

Poland: a giant with a skills gap: Poland has by far the largest talent pool, estimated at between 493,000 and over 586,000 professionals. This is a powerful asset, but the country is struggling with a significant skills gap. IT professionals account for 3.5% of the total workforce, which is lower than the EU average (4.5%). It is estimated that Poland lacks as many as 147,000 experts to reach the EU average.

Czech Republic: Hub of specialists: the Czech Republic has a solid base of nearly 230,000 ICT experts, representing 4.3% of the workforce – a figure close to the EU average. Renowned technical universities provide a steady flow of graduates, although they have to compete for talent with the powerful industrial sector.

Hungary: Stability and qualifications: In Hungary, the share of ICT professionals in employment is 4.2%, also close to the EU average. However, the annual growth rate of these professionals (2.4%) is slower than in the EU (4.3%) , suggesting a stable but less rapidly growing talent pool.

Romania: The density paradox: Romania has a large and highly valued talent pool of between 202,000 and 226,000 professionals. The country boasts the highest number of certified IT professionals per capita in Europe. Paradoxically, their share of the total workforce is the lowest in the group at just 2.8%. In addition, Romania faces a ‘brain drain’ problem, which poses a serious challenge to keeping top talent in the country.

This talent flow dynamic is fundamental to long-term development. The phenomenon of ‘brain drain’ in Romania stands in contrast to the ‘brain inflow’ in Poland, which is becoming an attractive place to work for professionals from other countries, including Ukraine.

An economy that loses talent often exports junior and mid-level professionals, which undermines its ability to create complex, high-margin products locally. In contrast, a country attracting talent can accelerate its march up the value chain by importing experienced experts.

This indicates that the Polish ecosystem may mature faster, while the Romanian ecosystem, if not reversed, may remain more focused on the provision of outsourcing services.

Map of Wages: Clash of the four capitals

Salaries are a key competitive factor in the talent market. A comparison of rates in the region’s main technology hubs reveals significant differences.

Warsaw bonus: Polish salaries are among the highest in the region. A senior programmer on a B2B contract in Kraków or Warsaw can expect a salary in excess of PLN 26,000 net per month (around EUR 6,000). Even on an employment contract, senior salaries exceed PLN 12,000 net (around EUR 2,800).

Prague competitiveness: Czech salaries are also very high. The typical range for IT professionals is between CZK 43,130 (approximately EUR 1,730) and CZK 122,874 (approximately EUR 4,930) per month. The best-paid roles, such as Data Scientist, can bring in an annual income of CZK 1.2 million (approximately EUR 48,150). The average annual salary for a software engineer is around EUR 55,600.

Budapest’s value proposition: Hungarian salaries offer a better cost/quality ratio. The average salary for an IT specialist is around EUR 1,800 per month , while a software engineer in Budapest earns an average of EUR 40,400 per year. This makes Hungary much more affordable to build a team than Poland or the Czech Republic.

Rising costs in Bucharest: Romanian wages are rising fast, but still offer a cost advantage. The average salary in the technology industry is EUR 3,402 net per month. The general range for IT is between RON 4,647 (approximately EUR 930) and RON 16,879 (approximately EUR 3,390) per month. However, these rates are further bumped up by the total exemption from income tax up to a certain threshold, which significantly increases the net salary.

The prevalence and high rates of B2B contracts in Poland are not just a billing method, but symptomatic of a mature, highly competitive senior talent market. This model gives maximum flexibility and earning potential to the best professionals, but at the same time creates instability for employers and leads to a more transactional relationship with employees.

In contrast, the dominance of traditional employment contracts in Hungary and the Czech Republic (83.5% and 67% in IT respectively) suggests a more stable, corporate labour market. This means that companies in Poland need to adopt a different HR strategy, focusing on offering attractive projects and top salaries, while in the Czech Republic and Hungary more emphasis can be placed on long-term career paths and company culture.

A list of coveted expertise: Who’s on top?

Across the region, there is a huge demand for specialists in areas such as artificial intelligence and machine learning (AI/ML), data analytics (Data & BI), cyber security and DevOps. It is these roles that are the highest paid.

However, each country also has its niches in which it has achieved a leadership position. Poland is a global powerhouse in the production of computer games (gamedev), with giants such as CD Projekt RED at the forefront. The industry generates more than EUR 500 million in revenue, creating an ecosystem of talent in game design, programming and graphics that is unique in the region.

Romania is rapidly developing its own gamedev scene, attracting global players such as Amazon Games, which has opened a new studio in Bucharest. The country is also strong in the Fintech sector, with the capital generating 77% of the industry’s turnover in the country.

The Czech technology scene fits perfectly with the needs of its industry base, targeting areas such as cyber security (Avast originated from here) and enterprise software. Hungary, on the other hand, with its high adoption rate of cloud and data analytics by corporations, generates a strong demand for data architects, cloud engineers and enterprise systems specialists such as SAP.

The innovation frontier: start-ups, outsourcing and investment

The future of any technology market depends on its ability to innovate, attract capital and integrate into the global ecosystem. This section examines the dynamics that are shaping tomorrow’s technology scene in Central and Eastern Europe.

The vibrant Venturelands: The startup race

Poland: Leader in terms of volume: Poland boasts the largest startup ecosystem in the group, with more than 1,251 companies. Warsaw is the dominant hub. The ecosystem is mature enough to have released nearly a third of all unicorns (companies with a valuation of more than USD 1 billion) in the CEE region. Funding, however, remains a challenge, with as many as 56% of startups reporting difficulties in obtaining it.

Czech Republic: An effective rival: Despite its smaller scale, the Czech ecosystem is highly rated, ranking 3rd in Eastern Europe, ahead of Poland. It is famous for startups in the areas of SaaS, Fintech and Healthtech and is the cradle of global success stories such as Avast and unicorns such as Rohlik and Productboard. A key challenge is the perceived lack of a sufficient number of high-quality projects by investors.

Hungary: a stagnant giant? Hungary has established companies such as Prezi and LogMeIn, but has struggled to maintain momentum in recent years. Total investment has stagnated at around EUR 54 million. Recently, however, there has been an upturn in the segment of early-stage AI-based startups, which could herald a rebound.

Romania: The unicorn factory: The Romanian ecosystem has been defined by the spectacular success of UiPath, the global leader in process automation (South Africa). This event has put the country on the map for international investors. The AI scene is particularly active, with large funding rounds for companies such as FintechOS. The ecosystem is heavily concentrated in Bucharest.

The success of UiPath has had a profound secondary impact on the entire Romanian ecosystem. Not only has it created a generation of experienced, wealthy angel investors and serial entrepreneurs (the so-called ‘UiPath mafia’), but it has also acted as a global proof of principle, reducing the perceived risk of investing in Romania in the eyes of international VC funds. This explains the impressive funding rounds for companies such as FintechOS and the general revival around the Romanian scene, which might otherwise seem disproportionate to the size of the market. This ‘unicorn effect’ is a powerful accelerator that allows the ecosystem to perform well above its nominal weight.

Global background: Strategic partner, not cheap labour

The entire CEE region is a leading global destination for IT outsourcing. Clients are increasingly shifting their focus from cost optimisation to access to high-end skills, innovation and cultural proximity. The regional talent pool exceeds 1.75 million engineers.

A stable business environment is a key asset. In the Doing Business 2020 ranking, Poland (40th), the Czech Republic (41st), Hungary (52nd) and Romania (55th) offer predictable conditions, an advantage over other global outsourcing hubs.

Poland is often recognised as a leader in IT competitiveness in the region thanks to its huge talent pool, business climate and strong exports. It is a major hub for the R&D centres of global giants such as Google and Microsoft.

The Czech Republic ranks among the top five countries in terms of the attractiveness of outsourcing, renowned for its high quality services and data security.

Hungary and Romania are attracting investors with their correspondingly low 9 per cent corporate income tax and tax exemptions for programmers, which, combined with a large talent pool, creates a powerful value proposition.

The strong presence of international R&D centres and outsourcing companies in Poland and the Czech Republic is not just a service industry; it is a key incubator for the country’s startup ecosystem. These centres train local talent to global standards, introduce them to global business practices and create a network of professionals who eventually leave to start their own product companies. A programmer working for five years in Google ‘s Warsaw office learns product management, scaling and international sales at a level not available in most local companies. Such a specialist, armed with unique skills, contacts and an understanding of the needs of the global market, is much more likely to succeed. In this way, the outsourcing sector is not a separate entity, but a fundamental pillar that feeds and accelerates the development of the domestic product and startup economy.

The role of the state: Catalysts for growth

The governments of all four countries actively support the technology sector through a variety of initiatives, including tax incentives, funding programmes and startup visas. Key policies, such as Romania’s income tax exemption for software developers or Hungary’s low CIT rate , are important competitive advantages. Poland and the Czech Republic are effectively using EU funds and national development agencies (such as PFR Ventures and CzechInvest) to fuel their innovation ecosystems.

Verdict: Poland’s position and the way forward

A synthesis of the data presented makes it possible to formulate a clear verdict on Poland’s position compared to regional rivals and to outline strategic perspectives for the entire region.

Regional SWOT analysis: Comparative scorecard

Poland:

- Strengths: Largest market and talent pool, diverse ecosystem (gamedev, enterprise), strong startup scene.

- Weaknesses: Significant talent gap, increasing wage pressure, high competition.

- Opportunities: Inflow of talent from abroad, opportunity to move up the value chain to more complex products.

- Threats: Loss of cost competitiveness to Romania/Hungary, market saturation in some areas.

Czech Republic:

- Strengths: Stable, mature market, highly qualified professionals, strong integration with industry, excellent business environment.

- Weaknesses: Smaller talent pool, slower growth, higher costs than some neighbours.

- Opportunities: Leverage the industrial base for innovation within Industry 4.0, become a hub for high-margin R&D centres.

- Threats: Competition for talent with powerful manufacturing sector, risk of stagnation.

Hungary:

- Strengths: Favourable tax environment, high adoption of advanced technologies in companies, strong value proposition.

- Weaknesses: Stagnation in startup funding, slower growth of talent pool, less dynamic ecosystem.

- Opportunities: Potential to become a specialised hub for AI and data science solutions for corporations, attracting cost-oriented FDI.

- Threats: Lagging behind regional leaders in startup innovation, political uncertainty affecting investor confidence.

Romania:

- Strengths: Top growth rate, high talent density, significant cost advantages, ‘unicorn effect’ after UiPath success.

- Weaknesses: Brain drain, less developed domestic market, infrastructure gaps outside major hubs.

- Opportunities: huge potential in the digitalisation of the country’s SMEs, becoming the gamedev hub of South East Europe.

- Threats: Talent retention, risk of overheating the economy, dependence on export markets.

Poland’s position in the CEE arena: Heavyweight champion under pressure

Poland remains the undisputed leader of the CEE technology scene in terms of scale, talent numbers and diversity of the ecosystem. The size of its market and depth of specialisation, especially in gamedev and enterprise software, are unrivalled.

However, leadership comes at a price. Poland faces challenges typical of a mature market: intense wage competition that undermines its cost advantage, and a critical skills gap that could stifle future growth. Poland is no longer the ‘low-cost’ option; it is the ‘scale’ option.

While Poland is leading the way, the competition is not sleeping. Romania challenges it in terms of growth and dynamism, the Czech Republic in terms of stability and specialised quality, and Hungary in terms of cost efficiency for corporate investments.

Collective strength: The future is regional

The future of the CEE technology scene will not depend on which country ‘wins’, but on how the region as a whole handles the transformation from a cost-driven outsourcing destination to a value-driven innovation partner. Poland, as the largest player, has a key role to play in leading this change, but its success is inextricably linked to the health and dynamism of its neighbours.