Poland’s economy is at the heart of a digital paradox. On the one hand, the country is dynamically consolidating its position as a key technology hub in Europe, attracting global investment and aspiring to become a regional leader. On the other hand, hard data paints a picture of a country on the digital front line. A Microsoft report ranks Poland third in Europe in terms of exposure to foreign-sponsored attacks, mainly from Russia. This contrast reveals a deep, structural weakness that could undermine the foundations of the country’s digital development: a widening competence gap in cyber security. This is not just a recruitment problem, but a strategic threat to the entire economy.

Poland on target

The scale of the threat facing Poland is unprecedented. In 2024, national incident response teams (CSIRTs) recorded a record 60 per cent increase in the number of breach reports, which translated into a 23 per cent increase in the number of realistically identified incidents. Each day, the CERT Polska team handled an average of nearly 300 attacks. Eurostat data is even more alarming: as many as 32% of Polish companies experienced cyber security incidents last year, which places Poland in the second disgraceful position in the entire European Union.

Polska jest na 3. miejscu w Europie pod względem narażenia na cyberataki sponsorowane przez państwa (głównie Rosję)

These external threats are hitting particularly fertile ground. Grant Thornton’s 2024 study, entitled ‘Castle of Paper’, reveals an alarmingly low level of cyber maturity among Polish companies. Although 40 per cent of companies have experienced an attack, almost half (48 per cent) do not regularly scan their systems for security vulnerabilities or log changes to IT systems. Most base their defence on basic tools such as antivirus and firewalls, while only 10-15% of companies have advanced monitoring systems (SIEM, XDR). There is thus a dangerous illusion of security: boards declare that cyber security is a priority , but a lack of competent staff prevents this awareness from being translated into real action.

Deficit of defenders

The problem of the shortage of specialists is a global phenomenon, with a worldwide shortage of more than 4 million skilled workers in the field. However, in Poland, the pressure is being felt particularly acutely. Demand for cyber security skills here has increased by 36% over the past year – the highest rate in Europe.

W Polsce popyt na kompetencje cyberbezpieczeństwa wzrósł o 36% – najwięcej w Europie

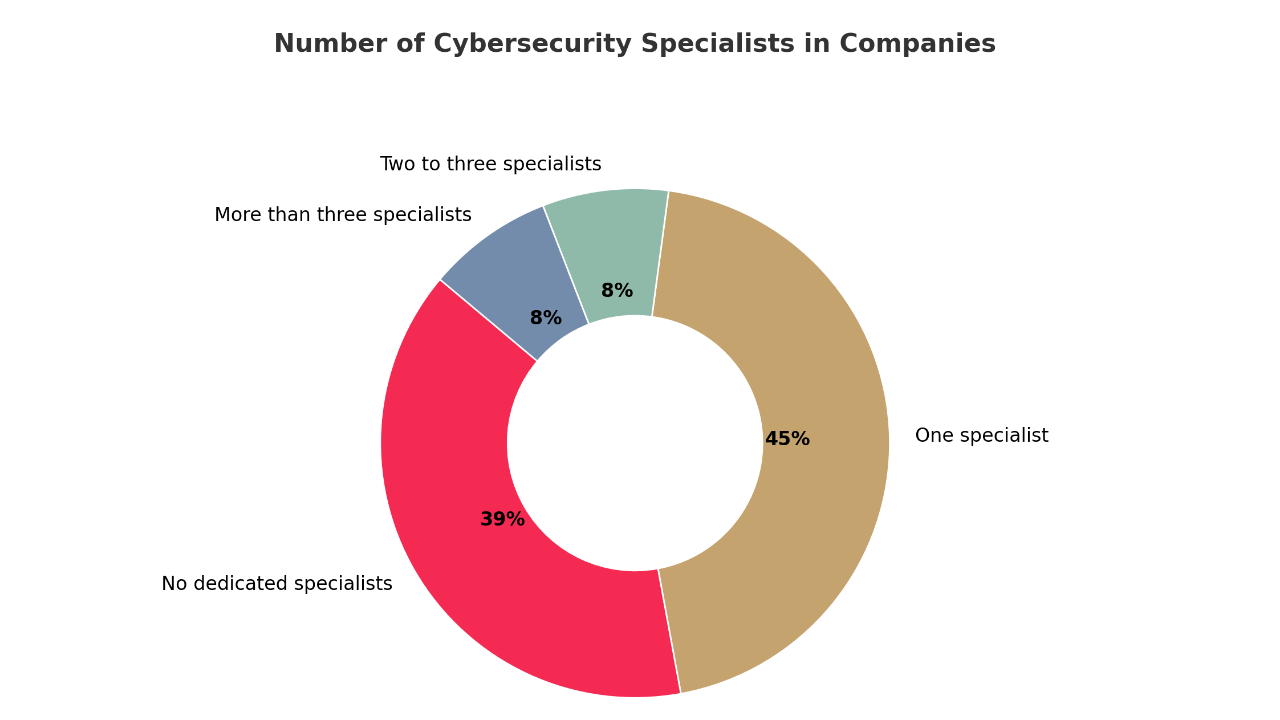

Estimates of the scale of the deficit in Poland range from 10,000 (according to the Polish Chamber of Information Technology and Telecommunications) to 17,500 specialists. However, these figures, based mainly on open vacancies, do not give the full picture. Data from the EU Cyber Security Agency (ENISA) shows that as many as 39% of Polish companies do not employ a single employee responsible for cyber security, and another 45% have only one such person. This means there is a huge latent demand. Many companies, especially in the SME sector, do not create vacancies because they are not yet fully aware of the need for such competence. As new regulations, such as the NIS2 directive, take effect, this latent demand will rapidly reveal itself, causing a shock to the labour market.

High cost of vulnerability

The skills gap translates into very tangible losses. There is a direct link between the skills shortage and the increasing number of successful hacks. As many as 87% of managers admitted that their company had experienced at least one hack, which can be partly attributed precisely to a lack of appropriate skills in the team.

The consequences are severe. More than half of companies that have been victims of an attack have suffered financial losses in excess of US$1 million. What’s more, there is a growing trend of executives being held personally accountable – in 51% of cases after an attack, executives were fined, lost their position or even imprisoned.

In addition to the direct costs, the skills gap acts as a silent saboteur, inhibiting innovation. Companies are afraid to implement new technologies, such as cloud computing or AI, because they do not have the human resources to secure them effectively. This innovation paralysis has real consequences: 20% of IT companies have had to refuse new projects due to a lack of specialists. In the long term, this weakens the competitive position of the entire Polish economy.

Labour market under siege

The imbalance between demand and supply raises salaries to levels not seen in other IT segments. Experienced professionals can count on salaries ranging from PLN 20,000 to even PLN 42,000 per month. Such high rates create a bipolar market. Large, international corporations can afford to compete for the best talent, effectively ‘draining’ them from the market. As a result, the backbone of the Polish economy – the SME sector – remains virtually defenceless, creating a systemic risk for the entire country.

The greatest demand is for analysts, engineers and security architects, with a particular focus on cloud security and incident response specialists.

Duże korporacje “drenują” rynek, zostawiając MŚP bez obrony – rośnie ryzyko systemowe

In search of a digital army

So how do we bridge the gap? Action is being taken on many fronts, but its effectiveness is limited. The formal education system is not keeping up with market needs. Employers point out that university graduates, while possessing sound theoretical knowledge, often lack key practical skills. As a result, the market ‘hacks’ the education system – companies and candidates create their own parallel education systems based on industry certifications, bootcamps and reskilling and upskilling programmes.

More and more companies are investing in the development of internal talent, which is often cheaper and faster than external recruitment. At the same time, the state is stepping up its efforts by creating specialised units such as Cyber Defence Forces and sectoral response teams, such as the CSIRT of the FSA for the financial industry. This is a step in the right direction, but carries the risk of further draining talent from the general market.