Professional burnout in the tech industry has ceased to be a taboo subject and has become a systemic crisis that threatens the foundations of innovation and the stability of the entire sector. It is no longer a matter of individual fatigue, but a silent epidemic of alarming proportions.

The research is clear: almost three-quarters (73%) of developers have experienced burnout at some point in their career. Earlier studies, such as the 2021 Haystack Analytics report, indicated an even higher percentage, reaching 83%.

The problem is just as acute in the Polish market, where symptoms of burnout affect as many as 70% of IT workers to varying degrees, with up to 42.1% of respondents at high risk.

When such a vast majority of the population experiences a negative phenomenon, it ceases to be an individual problem and becomes a systemic challenge. This normalisation leads to a vicious circle: new employees perceive burnout as ‘buying in’ to the industry, and companies may under-invest in prevention.

To add weight to this discussion, it should be noted that occupational burnout has been officially recognised by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and included in the ICD-11 International Classification of Diseases as an occupational syndrome.

Anatomy of burnout: The 3 dimensions of crisis

To effectively address burnout, it is essential to understand its nature. The WHO defines it as ‘a syndrome resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been effectively managed’. It is a phenomenon closely related to the work context.

The most influential model describing this syndrome, the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), distinguishes three fundamental dimensions.

- Emotional exhaustion: This is the central element of the syndrome, characterised by a feeling of complete depletion of energy resources. In the IT context, it manifests itself with thoughts such as: “I’m exhausted at the mere thought of starting another sprint” or “The morning status meeting is sucking all the energy out of me for the rest of the day”. It’s a sense of emptiness that doesn’t go away after the weekend.

- Cynicism and depersonalisation: This dimension describes a growing mental distance from work, accompanied by a negative or cynical attitude. In the IT world, cynicism can sound like: “Why make the effort and write clean code when this feature will be removed in six months anyway?”. Depersonalisation is treating colleagues and customers as anonymous objects, leading to a loss of empathy.

- Reduced sense of professional efficacy: The third pillar is a sense of lack of competence and personal achievement. The employee begins to evaluate his or her effectiveness negatively and feels that his or her contribution does not matter. In the IT industry, where progress is crucial, this dimension is particularly painful and can take the form of imposter syndrome, where even experienced technical leaders feel they are underperforming.

These three dimensions form a vicious circle. Usually it all starts with emotional exhaustion. To cope with it, the individual develops cynicism as a defence mechanism. However, this detachment leads to a decline in the quality of work, which becomes fuel for the third dimension: a reduced sense of efficacy.

The employee now has objective evidence that he is ‘failing’, which in turn exacerbates his exhaustion, closing a destructive cycle.

Battlefield analysis: risk factors in key IT roles

Each speciality has a unique ‘risk profile’ that shapes the day-to-day experience of professionals.

DevOps and SRE: engineers on constant call

DevOps and SRE specialists are the backbone of modern systems, but the role comes with a huge workload. The main stressor is the 24/7 work culture and ubiquitous on-call duties that blur the boundaries between work and personal life.

Another factor is the enormous complexity and fragmentation of tools – engineers manage an ‘endless jigsaw’ of technologies such as Terraform, Kubernetes and Jenkins. Added to this is the constant context switching, which can reduce productivity by up to 40%.

The burnout mechanism here is driven by chronic stress resulting from hyper-sensitivity and cognitive overload.

Cyber security: watchdogs on constant alert

Cyber security professionals operate in an environment with zero tolerance for error. A unique stressor is so-called ‘alert fatigue’ – fatigue caused by a constant barrage of alerts, most of which are false alarms.

The pressure is immense, as one mistake can lead to catastrophic losses. The situation is exacerbated by a global shortage of staff, meaning that existing teams are permanently overstretched.

This creates a sense of asymmetrical struggle: the defenders need to secure everything and the attackers need only one success. Burnout here is the result of operating in a long-term ‘fight or flight’ mode.

Project manager: conductor of an orchestra of chaos

PMs function at the intersection of different interests: the team, the client and management. The main source of stress is managing multiple projects at the same time, with more than half (52%) of PMs managing between two and five projects at once.

Equally taxing is emotional labour, i.e. absorbing frustrations and managing expectations. The constant need to make decisions leads to decision fatigue (decision fatigue).

The key element here is the disconnect between the enormous responsibility and the limited control over budgets, resources or changing requirements.

Developer (Frontend/Backend): between creativity and technological debt

The role of a software developer is saturated with unique stressors. One is the constant learning curve in the face of rapidly evolving technologies. But the strongest demotivator is the sense of wasted effort when weeks of work on functionality are rejected by the product department.

Added to this is the high cognitive load associated with working on a complex legacy code. The burnout mechanism is fuelled by the frustration of feeling that the work is more about fighting the system than creating real value.

QA / Tester: the quality guardian at the end of the chain

The role of the quality specialist is often underestimated, yet under enormous pressure. The biggest stressor is the position at the very end of the software development cycle. Any delays accumulate, drastically reducing the time for testing.

The role also suffers from a sense of undervaluation – the tester’s work remains ‘invisible’ as long as everything works, but when a bug makes its way into production, the QA department is most often blamed. Burnout in this role is the result of a toxic mix of high pressure, huge responsibility and low recognition.

The common denominator for the roles most at risk of burnout is a fundamental imbalance between responsibility and control. The DevOps engineer is responsible for the stability of the system, but does not always have control over the quality of the code being deployed.

The Project Manager is responsible for the delivery of the project, but does not fully control the resources. The tester is responsible for quality but has no control over the schedule. This discord is one of the most powerful chronic stressors in the workplace.

How do you build resilience against burnout?

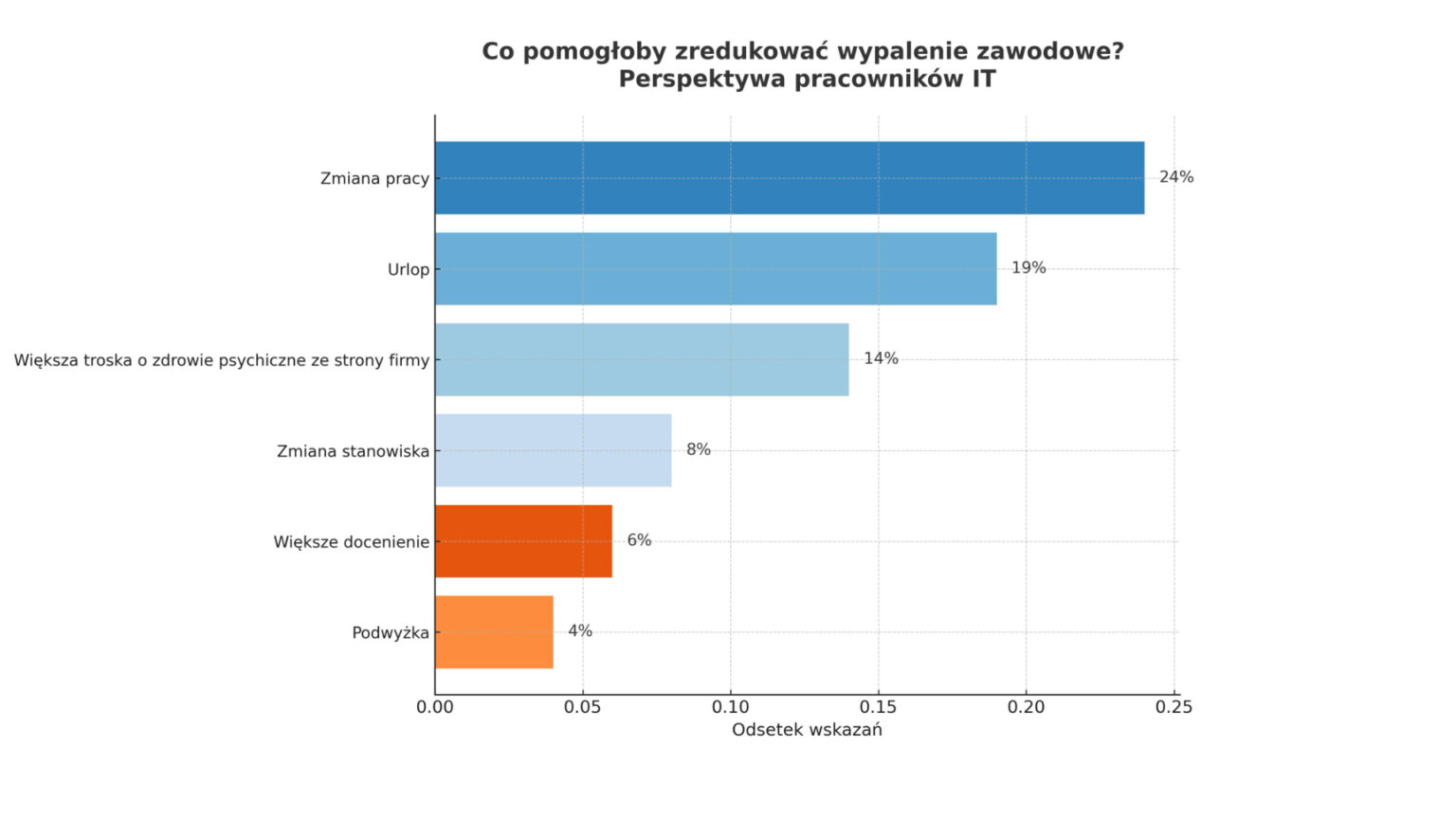

Combating burnout requires a two-pronged approach: strengthening individual resilience and, more importantly, fundamental organisational change.

- Conscious boundary-setting: It’s more than ‘work-life balance’. It’s about actively managing your own energy, scheduling blocks for deep work and regular digital detoxes. In doing so, it is important to remember that although 70% of developers code at weekends for pleasure, this can lead to blurred boundaries and prevent full recovery.

- Managing cognitive load: Methods such as the Pomodoro Technique or the conscious reduction of context switching can reduce daily overload.

- Normalising seeking support: Open communication with a supervisor and the use of psychological support are signs of maturity, not weakness.

- Build a culture of psychological safety: An environment must be created where employees can talk openly about problems without fear of punishment. Leaders need to model healthy behaviour – taking leave and respecting working hours.

- Process and tool optimisation: Investments in simplifying the tool chain (DevOps), automating testing (QA) and systematically reducing technical debt (Developers) are direct attacks on sources of stress.

- Ensuring a balance between responsibility and control: The level of responsibility must go hand in hand with an appropriate level of autonomy and control over one’s own work. Regular feedback helps to correct any imbalances.

- Actively promote regeneration: Companies should realistically encourage the use of holidays (and not contact employees during them) and offer flexible working arrangements.

Professional burnout is a signal that legacy working models in IT have reached their limits. It is time to stop treating employees’ mental health as a cost and start seeing it as a key investment in the most important resource the technology industry has: human talent, creativity and a passion to create.