In the digital arms race, there is a moment of absolute advantage for the attacker – the moment when a previously unknown vulnerability in software is used for the first time to launch an attack. This is ‘zero-day’.

For security teams, this is the worst possible scenario: they are faced with a threat they did not know existed, against which they have no ready defence, and the software vendor has not yet had time to prepare a ‘vaccine’ in the form of a security patch. During this critical window of time, which can last for days, weeks or even months, attackers operate with impunity, with an open path to the most valuable company assets.

Zero-day attacks are not theoretical musings, but a brutal reality. Incidents such as the crippling attack on MOVEit Transfer software have shown that a single, unknown vulnerability can have a knock-on effect, leading to the theft of tens of millions of people’s data and exposing thousands of companies to financial and reputational damage . This proves that the stakes in this race against time are extremely high, and understanding the anatomy of this threat is crucial for every IT department today.

Vulnerability lifecycle: from a bug in the code to a global incident

To effectively defend against zero-day attacks, it is essential to understand their lifecycle. Although these terms are often used interchangeably, each describes a different stage on the path from a bug in the code to a viable incident.

- Zero-Day Vulnerability (Zero-Day Vulnerability): This is a flaw in software code, operating system or device that is unknown to the manufacturer or, if known, has not yet been patched. The name zero-day refers to the developer’s perspective – it is the day they find out about a problem without having a solution ready.

- Zero-Day Exploit (Zero-Day Exploit): This is a specific tool – a piece of code or technique – created to actively exploit a vulnerability. An exploit is a ‘key’ that allows a ‘lock’ to be opened in the form of a vulnerability.

- Zero-Day Attack (Zero-Day Attack): This is the actual use of an exploit against a target. The name emphasises the perspective of the victim, who has exactly ‘zero days’ to prepare for defence.

The process from gap creation to gap patching can be divided into several key phases:

- Emergence and release: Software containing a hidden flaw is made available to users. The vulnerability exists but remains undiscovered.

- Discovery: The existence of a vulnerability is identified. The discoverer may be an ethical researcher, the manufacturer itself or – the worst-case scenario – a cybercriminal.

- Creating an Exploit: A theoretical vulnerability is transformed into a ready-to-use attack tool.

- Disclosure: Information about the vulnerability becomes known. In a responsible model, it goes to the manufacturer; in a malicious scenario, it goes to the black market or is exploited in secret.

- Issue of a fix: the manufacturer publishes an update that eliminates the flaw.

- Patch installation: The vulnerability lifecycle ends when users install the patch, closing the exploitation window.

A critical factor is the time gap between the discovery of a vulnerability by a malicious actor and the widespread installation of a patch. The entire strategy of zero-day attacks focuses on maximising this window.

Threat landscape 2023-2024: changing objectives and tactics

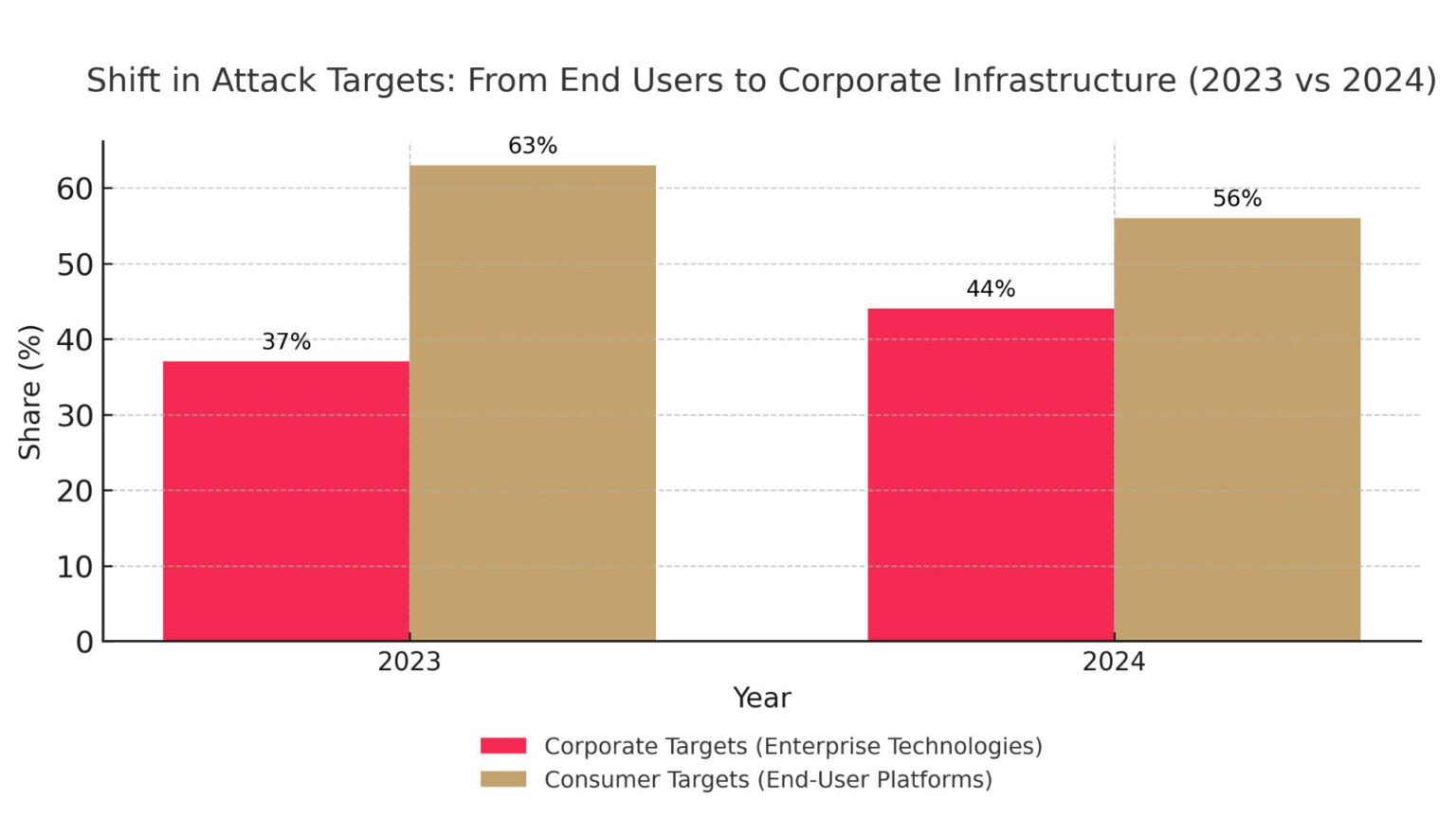

Analysis of recent years’ data, in particular from Google Threat Analysis Group (TAG) and Mandiant reports, reveals a fundamental transformation in attackers’ strategy. After a record-breaking year in 2021 (106 exploits), there were 97 exploits in 2023 and 75 exploits in 2024. However, these figures hide a more important trend: a strategic shift in objectives.

We have seen a dramatic decrease in the number of exploits targeting traditional targets such as web browsers and mobile operating systems . This is the result of years of investment in security by the technology giants, which have significantly increased the cost of creating effective exploits.

This shift has forced attackers to shift their focus to the heart of the corporate infrastructure. The percentage of zero-day attacks targeting enterprise technology has increased from 37% in 2023 to as high as 44% in 2024.

The targets were primarily edge devices and security software: firewalls, VPN gateways and load balancing systems . The compromise of one such device gives attackers a strategic entry point into the entire corporate network. This evolution is driven by simple economic logic – the ‘return on investment of an exploit’ is incomparably higher for an attack on a central piece of infrastructure than on a single user.

Case study: global crisis MOVEit transfer (CVE-2023-34362)

Nothing illustrates the new era of threats better than the global MOVEit Transfer software incident. It was a model example of a strategic hit to a key part of the digital supply chain.

MOVEit Transfer is a popular solution for the secure transfer of sensitive files, used by thousands of companies, government agencies and hospitals . Its central role has made it an extremely valuable target. The attackers, identified as the ransomware group Clop (FIN11), exploited a critical SQL Injection vulnerability that allowed remote command execution.

The operation was fast and automated. At the end of May 2023, the Clop group started a massive scan of the internet for MOVEit servers, automatically exploiting a vulnerability to gain access . They then installed a custom web shell (LEMURLOOT) as a backdoor and conducted automated data theft for several days . By the time the manufacturer released a patch on 31 May, it was too late for thousands of companies.

The impact was devastating. More than 2,700 organisations were affected by the attack, and personal data belonging to some 93 million people was stolen . The incident exposed a fundamental truth: the security of an organisation is inextricably linked to the security of its key software providers.

Zero-day economics: black market versus bug bounty

Behind every attack is a complex economic ecosystem. On the black market, knowledge of vulnerabilities is a valuable commodity. Prices for high-quality exploits are astronomical – a full chain of zero-click exploits for the iPhone can cost between $5 million and $7 million. Buyers are mainly government agencies, commercial spyware vendors (CSVs) and elite cybercrime groups.

An ethical alternative is bug bounty programmes, where organisations offer financial rewards to ethical hackers for responsibly reporting vulnerabilities. Platforms such as HackerOne and Bugcrowd coordinate this process, creating a legitimate market for the skills of security researchers . While rewards are important, many hackers are motivated by a desire to learn and build a reputation.

These programmes effectively limit the supply of less critical vulnerabilities on the black market. However, for the most powerful exploits, which are worth millions of dollars, bug bounties are economically uncompetitive. This reinforces the need to build defence strategies based on the ‘assume breach’ model (the assumption that an intrusion will occur).

Defence strategies for IT departments

In the face of zero-day threats that evade traditional defences, IT departments must adopt a multi-layered strategy based on prevention and effective detection and response.

Pillar 1: Prevention and strengthening of immunity

The aim is to make the IT environment as difficult to penetrate as possible.

- Update Management: Traditional monthly update cycles are outdated. The average time from vulnerability disclosure to exploitation has shrunk to just five days in 2024. It is essential to implement automated patch management systems and prioritise vulnerabilities from the CISA Known Exploited Vulnerabilities (KEV) catalogue.

- Zero Trust Architecture: The ‘never trust, always verify’ philosophy rejects the outdated ‘castle and moat’ model. Key elements are network microsegmentation, which limits attacker lateral movement, and the principle of least privilege, whereby each user and system has only the necessary privileges .

- Virtual Patching: This is a key tactic during the period when there is not yet an official patch. It involves implementing rules on Web Application Firewall (WAF) or Intrusion Prevention System (IPS) devices that block network-level attempts to exploit a known attack technique, allowing valuable time for the patch to be deployed.

Pillar 2: Detection and response to incidents

As 100 per cent prevention is not possible, having the ability to detect an attack quickly is crucial.

- Incident Response Plan (IRP): Having a formalised and rehearsed plan, based on a framework such as those developed by NIST, is the difference between a controlled response and chaos. The plan should include preparation, detection and analysis, containment and recovery, and post-incident phases.

- State-of-the-art tools (EDR/XDR): Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) and Extended Detection and Response (XDR) technologies are key. Instead of relying on signatures, they monitor and analyse the behaviour of processes across the infrastructure. Unusual activity, such as unauthorised privilege escalation, may indicate the use of an unknown exploit.

- Human factor: The most common vector of exploit delivery is spear-phishing – personalised emails designed to persuade the victim to click on a malicious link . Employees also need to be aware of watering hole attacks, where attackers compromise a legitimate website frequently visited by company employees to infect their devices. Regular training is an essential part of defence.

The future of fighting an invisible enemy

The anatomy of the zero-day attack has undergone a profound transformation. Threats have become more strategic, precisely targeting the heart of corporate infrastructure and driven by a profiled global ecosystem. A reactive approach based solely on patching is no longer sufficient.

Effective defence must evolve at the same pace. It is necessary to move to a model oriented towards architectural resilience. The Zero Trust philosophy is no longer an option, but a necessity. Ultimately, there is no single recipe for success in the fight against zero-day threats. It is an ongoing process, requiring a synergy of advanced technology, robust procedures and, most importantly, constant vigilance and readiness to adapt in the face of a constantly evolving enemy.