The contemporary debate on the automation of industry and services is entering a phase that historians of technology may in future refer to as the humanoid era. While for decades robots mimicking the human figure were mainly associated with ambitious but impractical research projects, today’s market and geopolitical realities give them a whole new status. What we are seeing today is not just an evolution of engineering, but a strategic technological arms race in which the total transformation of production and social processes is at stake. China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology compares this moment to the birth of personal computers or smartphones for good reason. We are facing a breakthrough that has the potential to redefine the global economic balance of power.

Underpinning this optimism is the fact that humanoid robots are the answer to the age-old problem of automation: the need to adapt the environment to machines. Until now, industrial robotics has been based on creating sterile, isolated ecosystems in which specialised arms operated within strictly defined parameters. Humanoids reverse this relationship. They are designed to function in an environment created by and for humans, without the need for costly demolition of walls, widening of passageways or modification of assembly lines. This adaptability makes them an ideal general-purpose solution, capable of taking over tasks in places where traditional automation has previously been economically unjustifiable.

From a geopolitical perspective, most symptomatic is the involvement of China, which sees this technology as key to maintaining its global factory status in the face of an ageing population and rising labour costs. As was the case with 5G technology, Beijing seeks to impose standards and dominate the supply chain for key components. For Western countries, success in this area could, in turn, mean an opportunity for a massive return of manufacturing to their home economies, or so-called reshoring. The robot, which does not require the reconfiguration of the shop floor and can operate the same tools as a human, becomes the catalyst for a new industrial revolution in which barriers to entry are rapidly lowered.

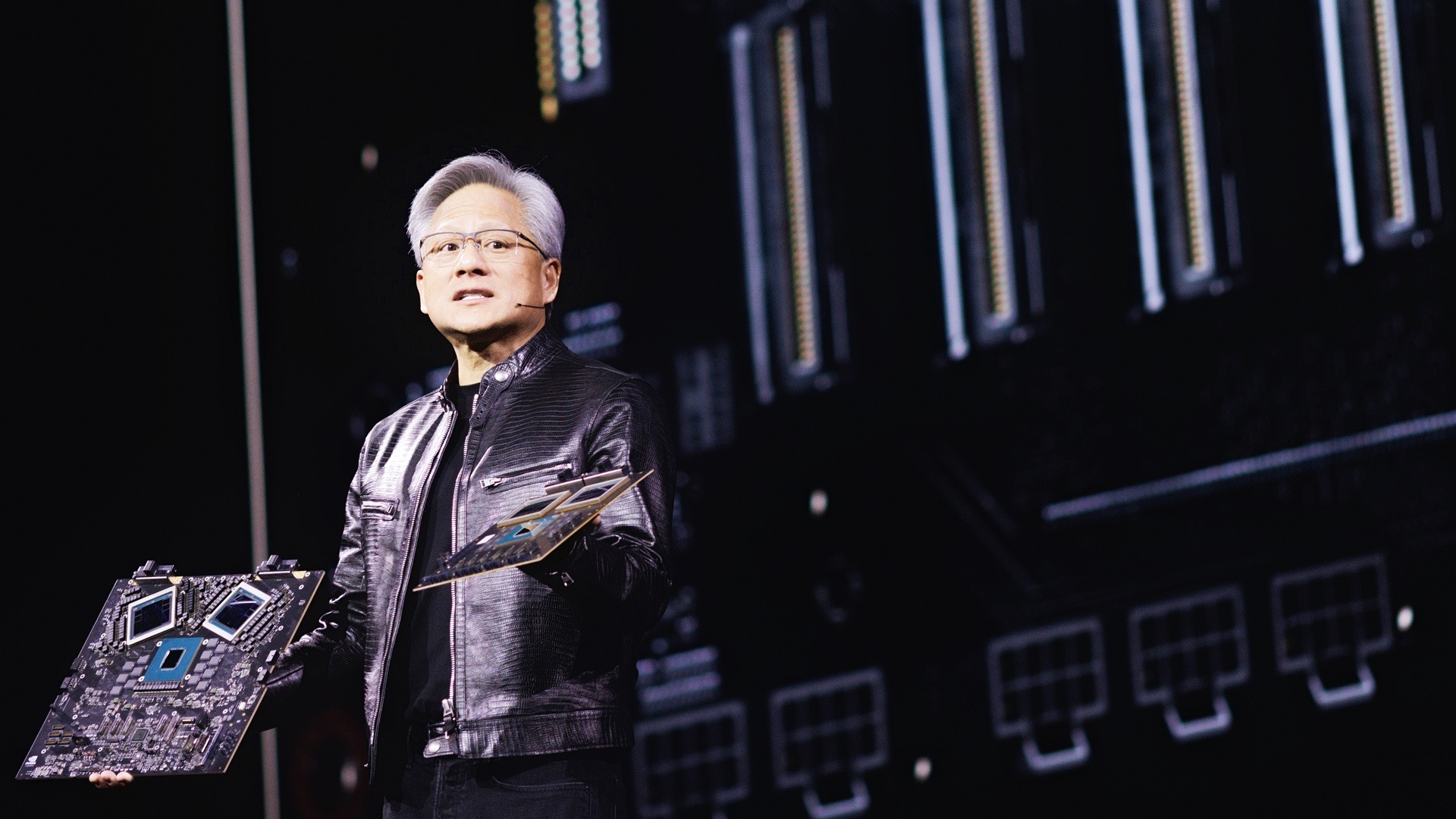

This breakthrough would not have been possible without the silent heroes of material progress. The incorporation of neodymium magnets has created a new generation of brushless motors that are lighter, faster and much more efficient than their predecessors. Combined with advances in control systems and hardware miniaturisation, today’s robots are gaining precision and coordination that seemed unattainable a decade ago. Importantly, these developments are leading to a gradual democratisation of technology. The emergence of more affordable models is fostering a wider ecosystem of innovation, where smaller research centres and companies can experiment with new applications without the need for giant budgets.

However, behind the glamorous demonstrations that regularly conquer social media, there is a reality that requires cool business analysis. Many of the jumps or complex choreographies presented online are still the result of tele-operations or numerous, carefully selected rehearsals. True autonomy remains the biggest software challenge. The key to achieving it lies in modern algorithms based on reinforcement learning and generative artificial intelligence, which allow machines to mimic natural human movement. Here, however, is another bottleneck: the need for gigantic amounts of data. The process of teaching a robot a seemingly simple action requires the recording of thousands of hours of human footage, which generates high logistical costs and raises complicated questions about data security and privacy.

From an operational perspective, one of the most mundane yet critical constraints remains energy autonomy. Current models, due to the enormous energy consumption of their numerous actuators and computing systems, are rarely able to operate for more than two or three hours without a break. In an industrial setting, where process continuity counts, this necessitates the development of new strategies for managing and charging a fleet of machines. In this context, the importance of technologies such as edge computing, which can offload the central units of robots and make them more energy efficient, is growing.

Just as important as technological barriers are social and psychological challenges. The term uncanny valley has ceased to be just an aesthetic curiosity and has become a real design problem. The sense of discomfort caused by machines that almost perfectly imitate humans can significantly delay their acceptance in the service, health or elderly care sectors. Business must therefore seek a balance between functionality and form that fosters trust and empathy, rather than creating fear. Responsible integration into the everyday environment will require not only great engineers, but also sociologists and ethicists.

Despite these difficulties, the direction of change seems inevitable. In the industrial sector, humanoids will not immediately replace specialised robots where pure speed matters, but they will bring invaluable flexibility to tasks that have hitherto been ‘too human’ for automation. In healthcare or logistics, they will serve as assistants freeing up staff time for higher value-added tasks. Already, pilots being carried out in Europe and Asia are exploring the safe co-operation of humans and machines within the framework of so-called collaborative robotics.

For business decision-makers, the conclusion is clear: humanoid robotics is just now leaving the phase of pure experimentation and entering the stage of market validation. This moment requires the promotion of clear standards and specialised training. It is not about succumbing to a momentary fascination, but about starting to plan the integration of these machines into existing value chains, based on hard metrics of usability and return on investment. Those organisations that begin to understand and test these solutions today will be at the top of the pile in the new global technological order tomorrow.