Edge computing is increasingly appearing in companies’ strategies as a response to operational and environmental needs. But is it really a ‘green’ alternative to the cloud and data centres? In practice, the opposite happens: green ambitions require investments that increase IT complexity and costs in the short term.

Paradigm shift: from centralisation to the edge

Just a decade ago, the data processing model in companies was simple: data flowed to central data centres or to the cloud, where it was analysed, processed and stored. Today, such a model is increasingly failing – not because technology is failing, but because the physical reality of how companies operate is changing.

On the one hand, data is generated much closer to physical processes – on production lines, in IoT devices, at checkouts, in fleet vehicles or vision systems. On the other hand, it increasingly does not make sense or possible to transmit this data to central centres. Response times are too long, connections too unreliable and costs too high. This gives rise to the need for processing at the edge of the network, or edge computing.

Edge is no longer a technological curiosity, but a growing category in IT architecture – driven not by ideology, but by necessity. Processing data where it arises is sometimes the only acceptable option: for example, in industrial SCADA systems that cannot tolerate interruptions or delays, or in environments with critical privacy requirements where data cannot leave the physical facility.

This shift in focus – from centralisation to localisation – is not without cost. It means that companies today have to operate hybrid environments: some computing is done in the cloud, some in a data centre and some on-site – often in locations unsuitable for IT hardware. This distributed landscape is not only a challenge for infrastructure teams, but also for ESG strategies. How do you measure the carbon footprint of a system that is physically spread across dozens of locations? How do you optimise it?

Edge computing is not replacing the cloud – it complements it. But the growing presence of edge infrastructure is forcing companies to rethink not only their data architecture, but also their fundamentals: where to process, how to measure efficiency and on what principles to build ‘green’ IT in a world that is becoming increasingly less centralised.

ESG as a new filter in IT decisions

Until recently, decisions about where and how to process data were the domain of IT departments and the CIO. Today, ESG teams increasingly also have a say in this. In companies that take their sustainability goals seriously, the choice between cloud, data centre and edge computing is no longer just a technical decision – it is becoming part of an environmental strategy.

It is no longer just about reducing CO₂ emissions from car fleets or investing in photovoltaics. More and more companies are starting to consider the impact of digital infrastructure on their overall environmental footprint. This means that IT infrastructure – often fragmented, invisible and managed inconsistently – is coming under the magnifying glass of ESG teams. As a result, a new decision filter is coming into play: how a given IT architecture affects energy efficiency, resource consumption and sustainability reporting capabilities.

In this context, edge computing appears to be a solution with potential: it allows the transmission of data over long distances to be reduced, which can translate into lower energy consumption and less strain on the network. Especially where links are weak or unstable, local processing can not only be faster but also more energy-efficient.

But this is only part of the picture. In order for an edge to truly support ESG objectives, it needs to be properly designed – and with this, things can vary. In practice, many edge solutions operate in backrooms of shops, industrial halls or containers with minimal cooling. Such environments are not only difficult to monitor, but also often energy-intensive and inefficient. Additionally, the lack of standardisation and automation makes it difficult for companies to accurately report on the environmental impact of edge.

From this perspective, the edge becomes not only an opportunity, but also a test of ESG maturity in companies. Can the organisation consider the sustainability impact of distributed infrastructure? Can it coordinate between IT, operations and ESG teams? And finally – is it prepared to invest in more sustainable edge solutions, even if the initial cost is higher?

ESG does not change the objectives of IT. It does, however, change the criteria by which these objectives are judged today.

A green edge is not always a cheap edge

In theory, edge computing can support sustainability goals – it reduces data transfer, reduces network load and allows energy consumption to be optimised locally. In practice, however, sustainable edge is rarely a cheap solution. On the contrary: in many cases, it implies significant costs – both investment and operational costs.

One of the main concerns is scale. Large, centralised data centres are designed with efficiency in mind – maximum power density, optimised cooling, full utilisation of resources. Companies invest in them consciously, planning for a long-term return. Meanwhile, the edge is often created ad hoc – in small locations with no data centre-class infrastructure. IT equipment ends up in cupboards in warehouses, back rooms of shops, industrial halls. There is a lack of air conditioning, energy management, automation. The result? Higher power consumption, higher losses, maintenance difficulties.

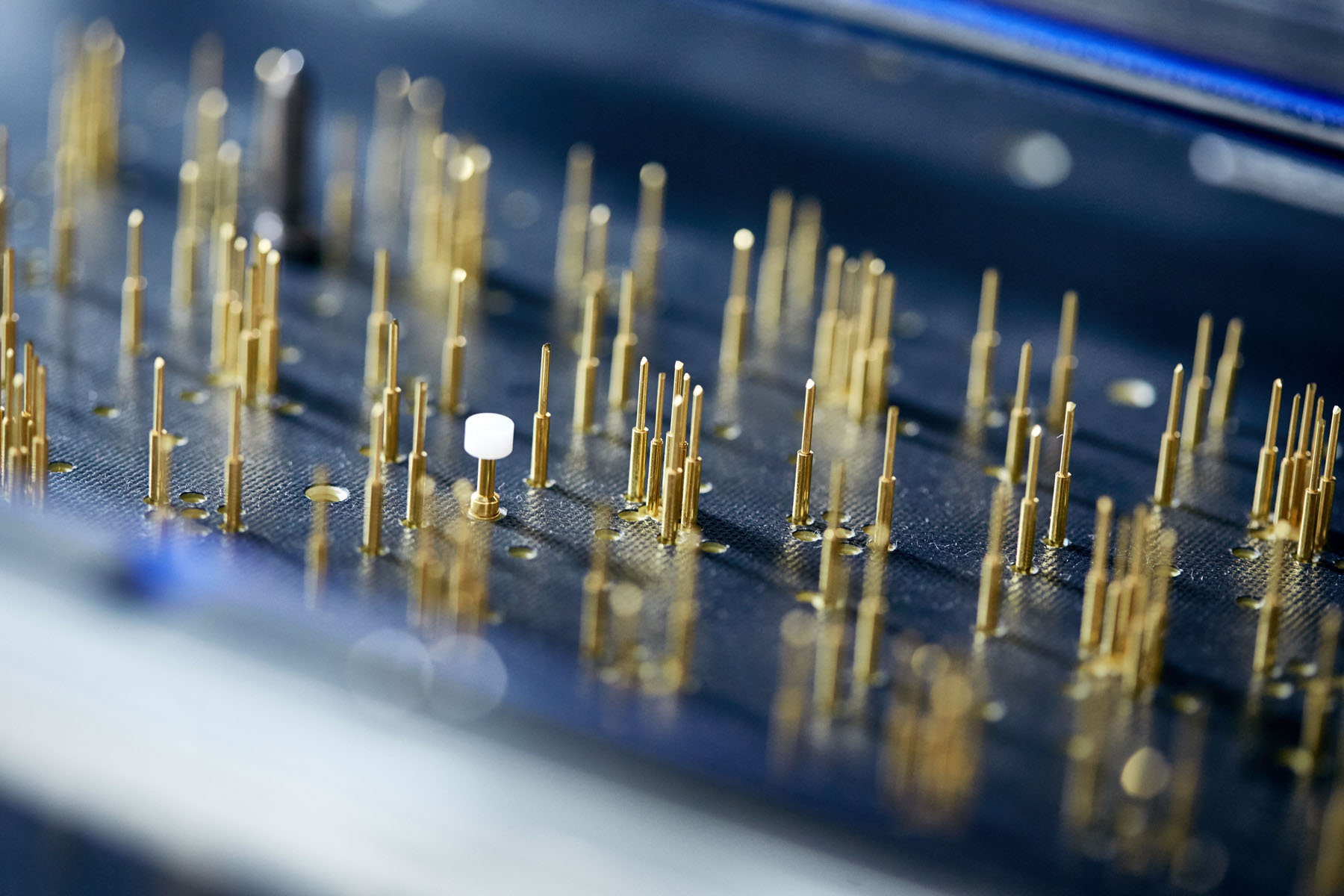

Added to this are the costs of retrofitting. Building a ‘green’ edge – with efficient cooling, heat recovery or a low-carbon power supply – requires the use of modern technologies, which do not come cheap. We are talking about servers with next-generation chips, liquid cooling, insulated enclosures or even micro gas generators. The same solutions that work well in hyperscale data centres do not necessarily make economic sense in a location with one or two servers.

The paradox is that edge – although designed to address the needs of speed and efficiency – can easily become a flashpoint in a company’s energy balance. This is why there is increasing talk of the need for standardisation and a service-based approach to edge computing. Companies do not want to build and manage dozens of distributed sites themselves – they prefer to buy edge as a service, with guaranteed performance and scalability.

The green edge is a challenge rather than a standard today. Only companies that treat it strategically – as part of a larger whole rather than a point solution – are able to make it realistically effective and sustainable.

Edge vs cloud: the invisible battle for efficiency

On a marketing level, edge computing and the cloud often function as complementary solutions – two poles of the same modern IT architecture. But beneath the surface there is a subtle battle going on: over resources, over performance, over control and over what ‘efficiency’ really means in the age of ESG.

The cloud, especially the public cloud, has an argument that is hard to dispute: economies of scale. In hyperscale data centres, every aspect of the infrastructure – from energy consumption to cooling – is optimised to the limit. Renewable power supply, advanced liquid cooling systems, automation, equipment lifecycle management – all these achieve levels of energy efficiency that distributed edge installations cannot match.

Meanwhile, edge often operates in isolation – in physical locations not designed for IT, with limited automation and difficult service access. Even if it limits data transmission over long distances, its per-unit energy consumption per operation is sometimes much higher than in the cloud. In other words: edge saves on transmission, but loses on processing.

This gap is particularly apparent when companies start to include indirect emissions – so-called Scope 2 and Scope 3 – in their ESG reports. The cloud enables accurate tracking and reporting of the carbon footprint; the edge – fragmented, difficult to standardise – can become a calculation gap.

However, this does not mean that edge loses the battle for efficiency. In some scenarios – e.g. IoT systems that process huge amounts of data locally – edge can realistically reduce the emissions from transmission and central processing. The key is context: type of application, intensity of operations, geographic location, and availability of alternatives (e.g. fibre vs. mobile transmission).

In practice, what is an energy-efficient edge for some companies may be an inefficient duplication of resources for others. Therefore, the battle between edge and cloud is not decided at the technology level – but at the strategy level. The most mature organisations are those that can assess not only TCO or performance, but also the carbon cost of each infrastructure decision. And this requires more than good architecture – it requires transparency, standardisation and a new definition of what ‘efficiency’ means in the ESG era.

When sustainable edge starts to pay off

Sustainability in edge computing is not the result of one technology or the choice of a particular platform. It is the result of a well-designed architecture, scalability and the realisation that edge is not a single device at the production line, but a component of a larger ecosystem. Only then does it start to balance not only energy-wise, but also business-wise.

This is why more and more companies are moving away from self assembled edge installations and turning to service models – such as Edge as a Service (EaaS) or Multi-Access Edge Computing (MEC). In both cases, local data processing takes place in miniature data centres managed by specialised providers: telco operators, cloud providers, infrastructure integrators. From the companies’ point of view, this is convenient: they get local computing capacity without having to invest in hardware, cooling, security or monitoring.

The gain is also environmental. Shared edge infrastructure – especially when integrated with 5G – makes it possible to significantly improve energy efficiency, mainly through better resource utilisation and automation. An example: mobile operators that install local computing clusters (MEC) for 5G networks often also offer them as a service to companies – gaining operational synergies and increasing equipment utilisation.

But edge only starts to pay off realistically when its data is used for more than just local processing. A key element is integration with and secondary use of IoT data: for energy optimisation, better building management, logistics planning or predictive infrastructure maintenance. An example? Analysing sensor data in production halls can lead to real savings – such as automatically shutting down cooling systems, reducing heating in unused areas or predicting equipment failure.

A well-designed edge not only ‘works’, but becomes a launching point for operational transformation. In this sense, a sustainable edge is not an investment in technology, but in an organisation’s ability to transform data into decisions – faster, closer to the source and in line with ESG goals.

It is then – and only then – that its cost ceases to be a burden and begins to bring value.

Edge computing is entering a new phase – no longer as an experiment or complement to the cloud, but as a viable pillar of IT infrastructure. In this new set-up, it is becoming increasingly difficult for companies to avoid the question of not only whether to build edge, but how to do so in a sustainable way – technologically, environmentally and financially.

Contrary to popular belief, edge is not by definition a ‘green’ solution. In many cases, it can even exacerbate the problems of resource fragmentation, low energy efficiency and the difficulty of monitoring the carbon footprint. At the same time, it is difficult to ignore – there are areas where the cloud or centralised data centres cannot meet operational requirements. Edge is therefore becoming not an option, but a necessity.

The key turns out to be not the choice of technology itself, but how it is implemented. Local edge installations that arise spontaneously, without strategy or standards, generate higher costs and more operational chaos. In contrast, a well-designed edge – as a service, with IoT data in mind, oriented towards the secondary use of information – can realistically support ESG goals and, in the long term, also generate savings.

Companies that treat edge solely as a low-latency response may overlook its transformative potential. Those that consider it in the broader context of data strategy and sustainability are beginning to build an edge that will be difficult for the rest of the market to catch up with.

The sustainable edge is no longer a question of ‘is it worth it’. It is a question of ‘are we ready to implement it properly’.